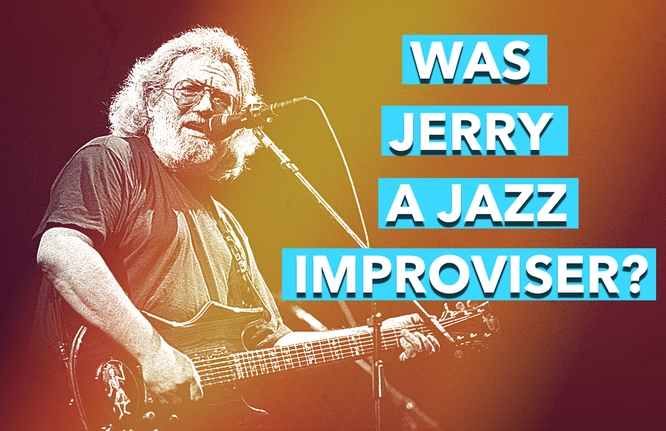

Jerry Garcia was one of the most iconic musicians of the 20th century.

He was a multifaceted professional: a singer, songwriter, pedal steel player, 5 string banjoist.

Jerry is most well known as a guitar player who blended rock, folk, blues, county, bluegrass and countless other influences into a style that was all his own.

Despite devoting his life to pushing musical boundaries with the Grateful Dead and a host of other groups and musicians, he is often viewed by onlookers as someone who noodled, and spent his time on stage running scales.

Even Mike Gordon of Phish famously threw his two cents on this idea in The Phish Book by Richard Gehr:

“When I was a freshman at the University of Vermont in 1983, I traveled to Dead shows when I should have been studying electrical engineering. A guy in my dorm used to razz me by saying ‘Getting together and playing like the Dead is the easiest thing in the world. You just go up and down mixolydian scales together.’ There’s an element of truth to that, of course, but you also need years of experience or moments of true abandon to when to go up the scale and when to come down.”

Almost every Grateful Dead fan I’ve ever met, particularly ones that are musicians, has had a conversation similar to this at one time or another with a non-fan.

Arguments and other instruments aside, Jerry’s unique improvisational approach on guitar is what made him stand out among his peers.

Although Garcia may not have been a traditional jazz guitar player, he inherently used jazz approaches in his playing, fueled by a lifetime of being a lover of the genre.

As Miles Davis said in his memoirs:

“So it was through Bill [Graham] that I met the Grateful Dead. Jerry Garcia, their guitar player, and I hit it off great, talking about music – what they liked and what I liked – and I think we all learned something, grew some. Jerry Garcia loved jazz, and I found out that he loved my music and had been listening to it for a long time.He loved other jazz musicians too, like Ornette Coleman and Bill Evans.”

In an October 1978 issue of Guitar player, Garcia also mentioned that he was a huge fan of several other jazz Titans such as Pat Martino, George Benson, and Al Di Meola, and confessed of having an obsession with the music of both Duke Ellington and Art Tatum.

Sound Grammar

Although Jerry played with fusion groups, made records of standards, and shared the stage with jazz legends and luminaries such as Ornette Coleman and Branford Marsalis, I often hear Jerry get written off as someone who didn’t execute or even understand the language of jazz.

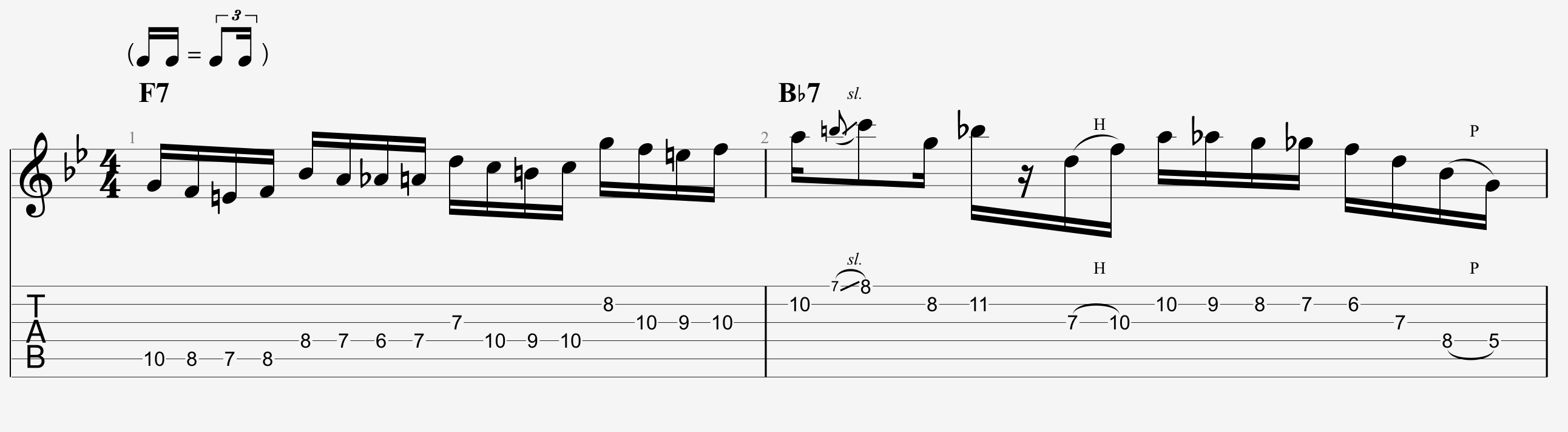

As a starting point, lets take a few seconds of a great jazz solo and see some of the approaches that a master jazz improviser would use.

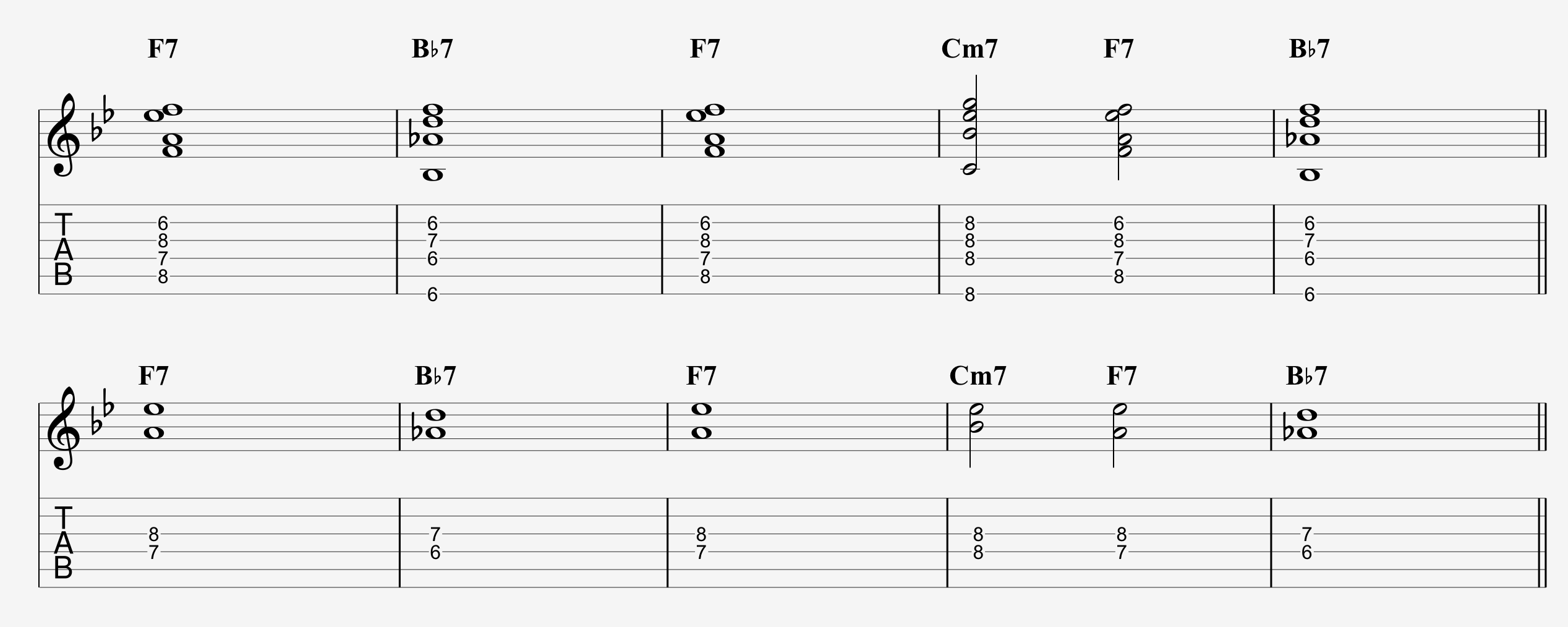

Here’s a few seconds of improvising from “Society Red” an F blues written and originally performed by Dexter Gordon in 1961.

We can clearly see five devices, or ideas, that occur in this solo that are a staple of jazz improvisation.

- Chord tones

- Extensions

- Enclosures

- Guide Tones

- Chromatic Connections

This style of jazz is typically known as hard bop. It mixed much of the musical grammar of bebop with the more relaxed feel of gospel and blues, and created a timeless balance of music that was cerebral yet highly soulful.

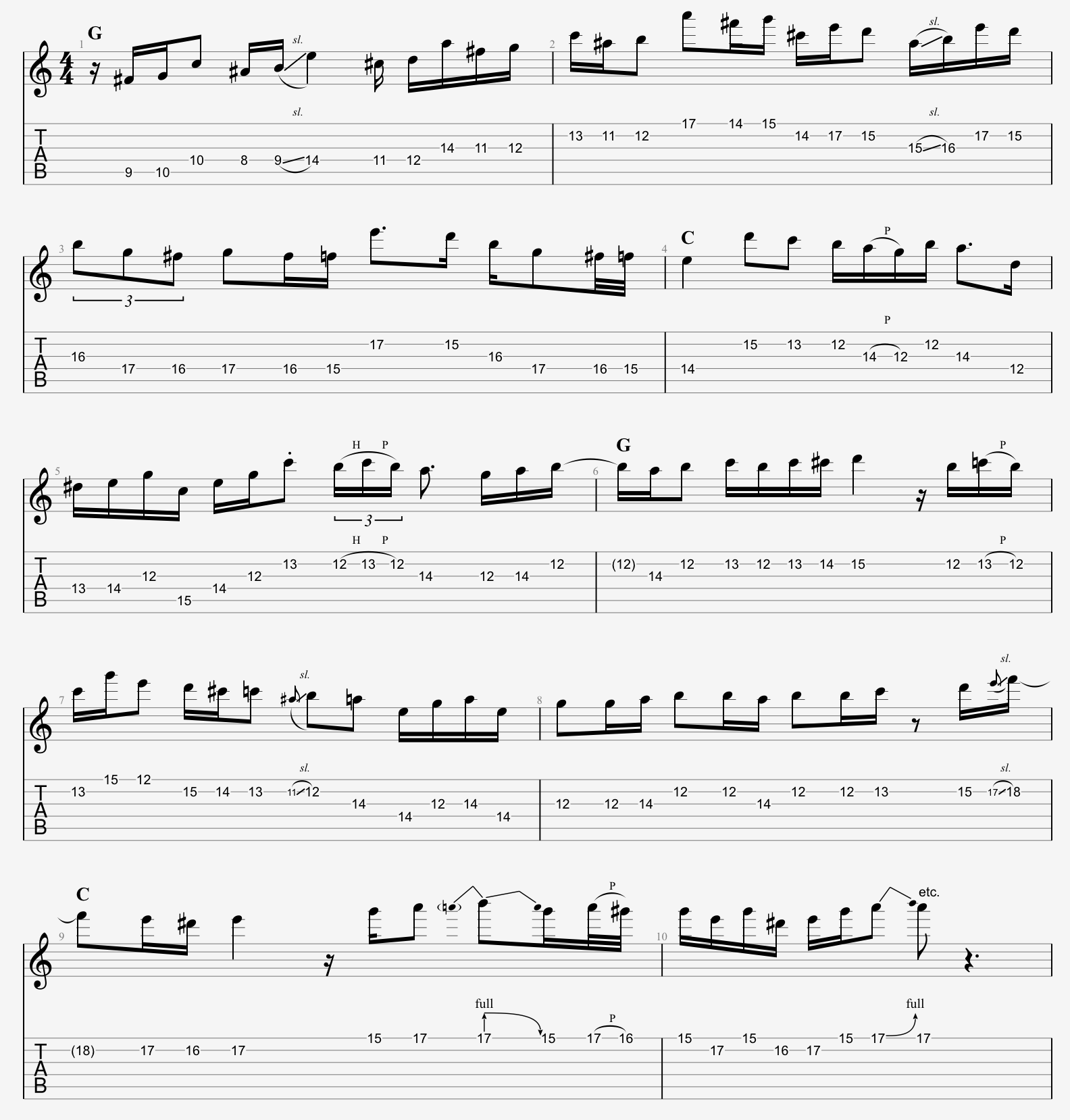

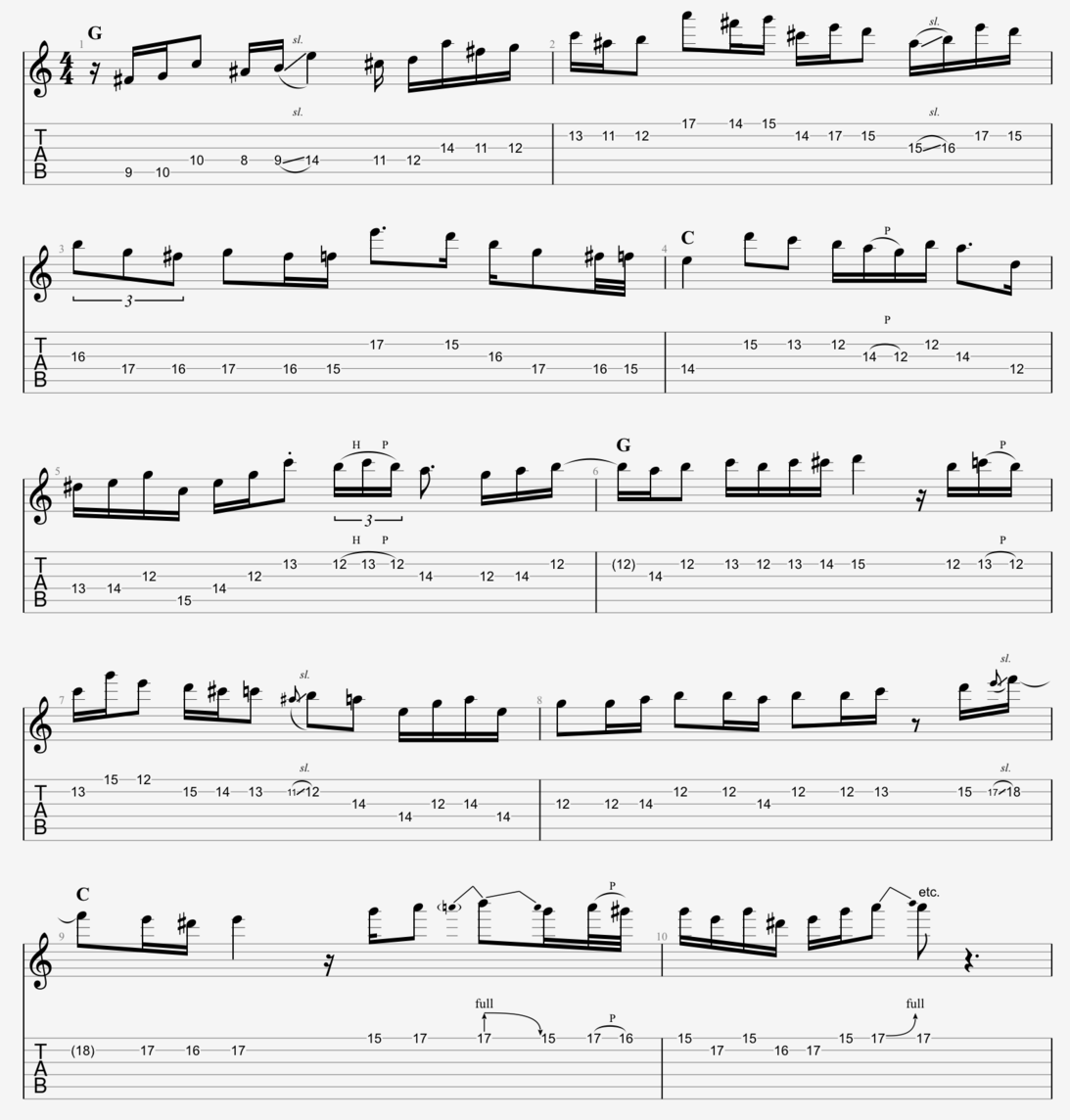

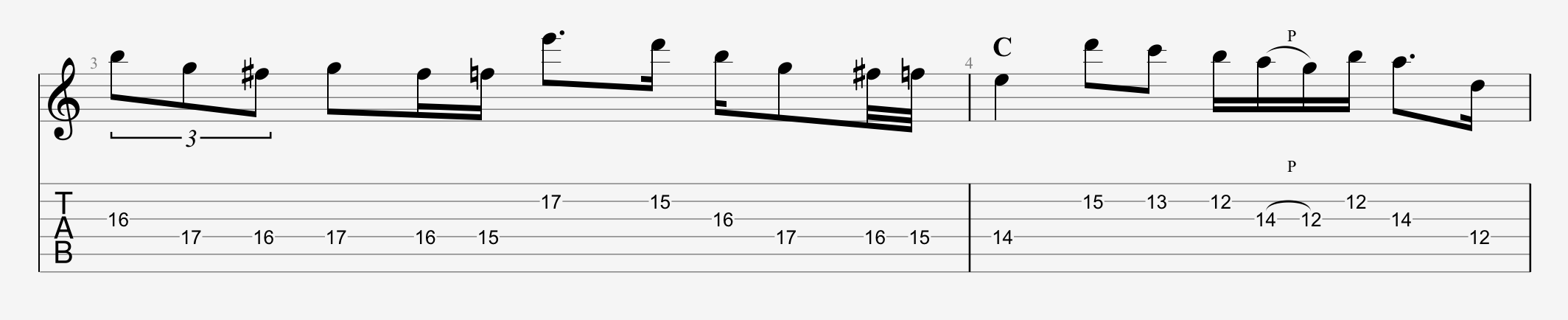

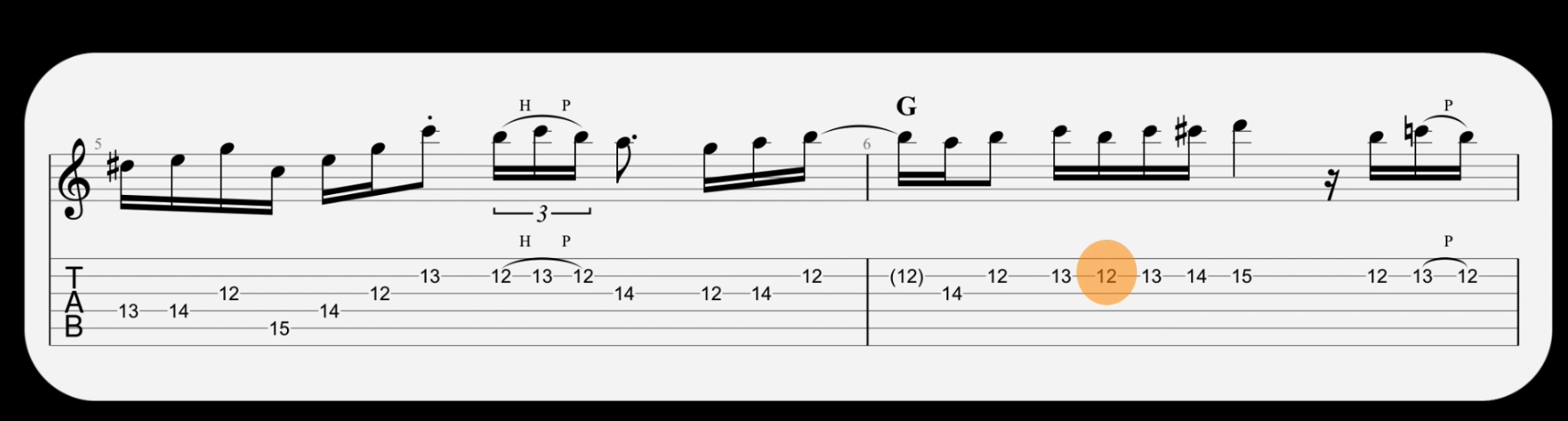

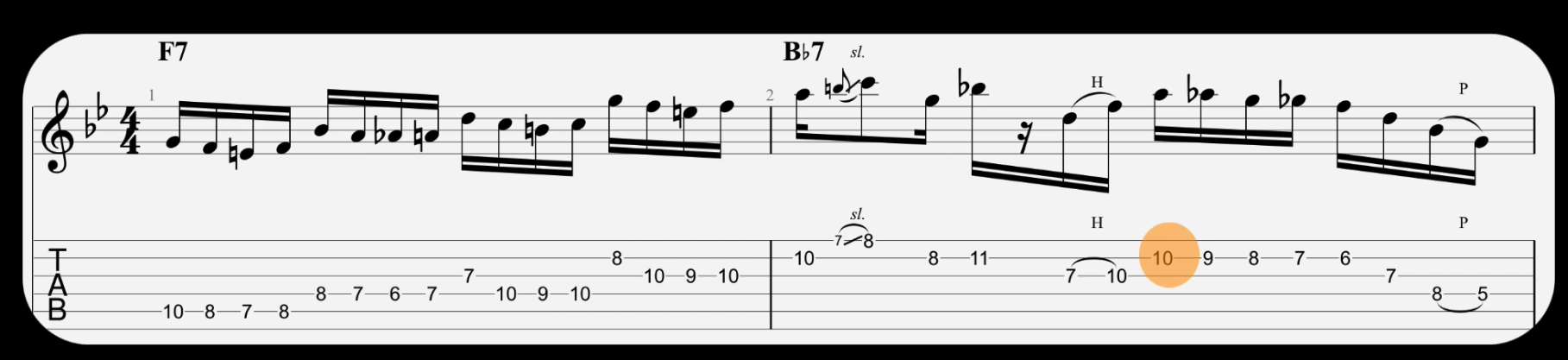

Let’s compare Dexter’s solo, with a Jerry Garcia improvisation From May 8, 1977 at Cornell University with the Grateful Dead.

We can pinpoint every one of these five musical devices in just these few measures of Garcia’s solo as well:

Chord Tones

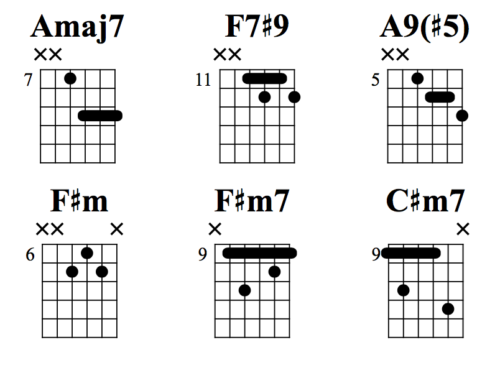

In these examples, Both Jerry and Dexter use one of the most central concepts in improvisation, which is focusing on chord tones.

Chord tones are merely notes, or tones, that exist within a chord.

In Society Red, the first chord is an F7, which contains the notes F, A, C, Eb. These comprise four chord tones – the root, major 3rd, fifth and flat seventh degrees.

Dexter hones in on the root, third and fifth when he gets to this F7 chord.

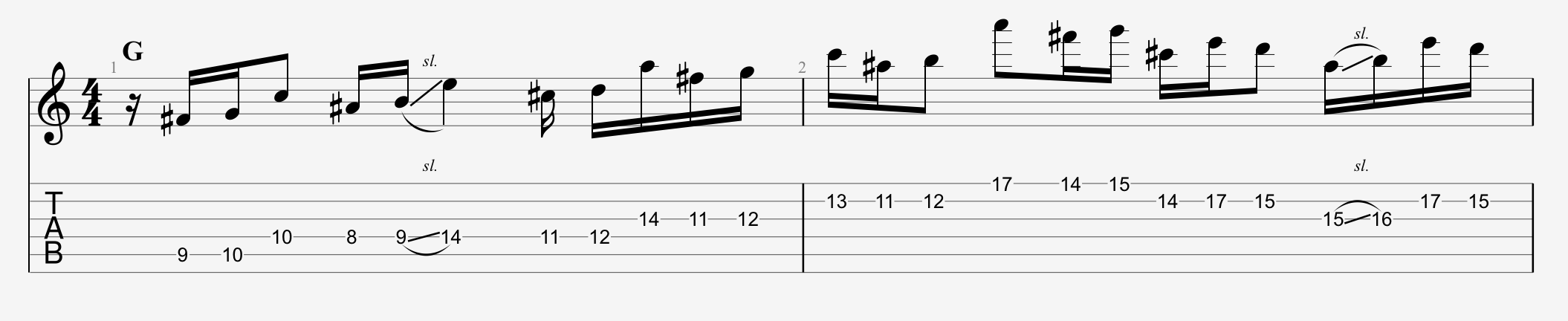

Just like Jerry hones in on the root, third, and fifth of the G chord, the first chord in They Love Each other’s solo section.

But both of them don’t just play these chord tones alone. They surround, or enclose, them with other notes to spontaneously create beautiful melodies.

At first it may sound like this is some exotic, advanced jazz scale that he uses to play such an elegant line, when, in fact, he uses a very simple formula to enclose chord tones.

He plays up a scale tone, lands on the chord tone, travels down to a chromatic tone below, and lands back on the chord tone.

Jerry uses almost the exact same enclosure formula to start his solo on the Cornell 1977 They Love Each other, with an off kilter phrase that is just bursting with color.

We see that he approaches the root from a chromatic half step below, plays up a scale tone of the 3rd, another half step below, and then lands on the third.

He then slides up the neck and continues the formula –

- Up a scale tone, down a half step below of the chord tone, and then lands on the fifth of G.

- Up a scale tone, down a half step from the root and then, lands on the root.

- He does the same thing with the third, then the root, and back down to the fifth.

What sounded an out-there scale, is in reality, just a classic jazz formula for enclosing chord tones!

Extensions

Jerry continues his solo:

There are a few notes in this phrase that particularly stand out – Thee note on the 17tth fret of the B string in Bar 3 that Jerry lands on, is the 6th of G also known as the 13th.

This 15th fret of the B string in bar 4 (the note D) that Jerry lands on here is the 2nd degree of C, also known as the 9th.

Why do chord tones have different names? What is the point of giving them two number designations? Isn’t music complicated enough already??

This gets us to one of the biggest distinctions of how jazz improvisers view the very essence of melody and harmony.

Scales and modes are typically absorbed by musicians as a linear idea.

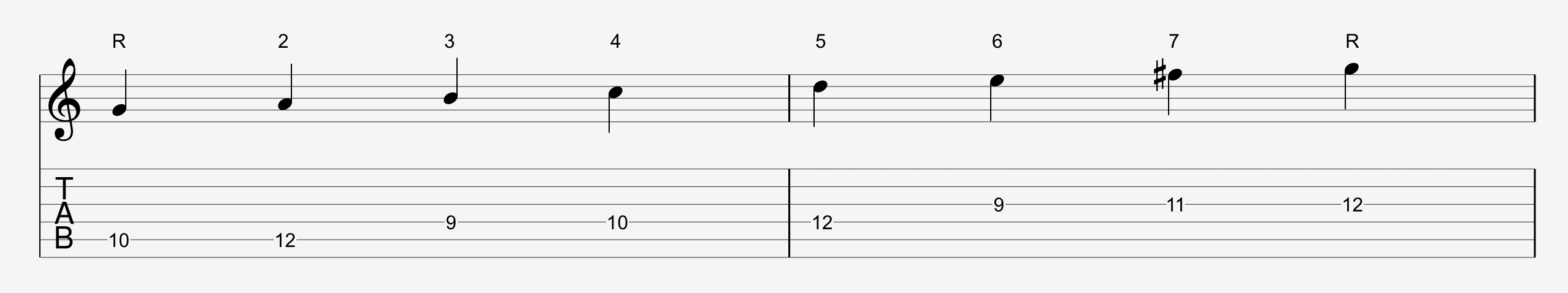

Here’s the G major scale, played from root to root, ascending one scale tone at a time.

But jazz improvisers don’t only view a scale in this fashion.

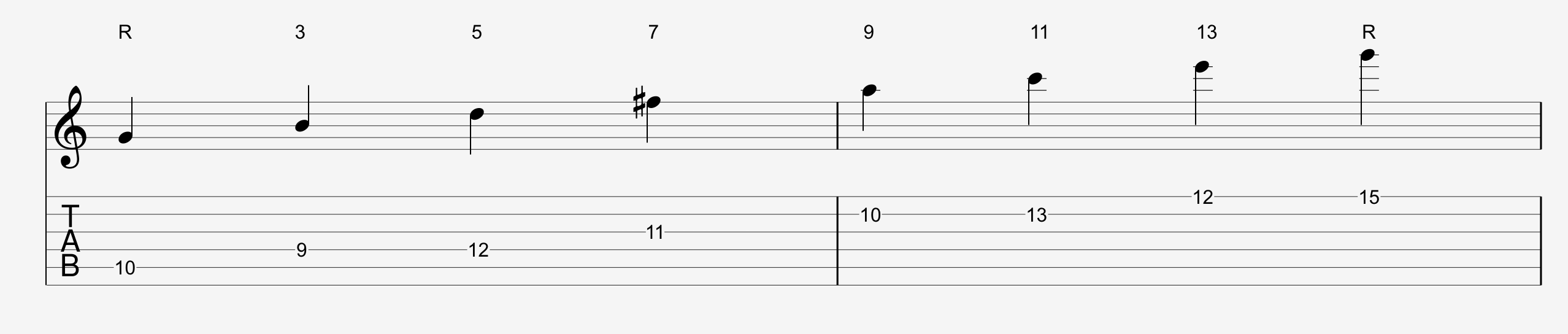

And that’s because chords are typically built of stacked thirds, so why can’t scales be constructed the same way?

What happens when we build the G major scale on thirds?

It turns out that get the exact same notes that we had in the linear model, but it gives a fuller picture of the sound and function of each of the notes in the scale.

The 1st, 3rd, 5th, and 7th happen consecutively. Then we get the extensions – the 9th, 11th and 13th, which are just the 2nd, 4th, and 7th degrees but, in this case, up an octave.

These extensions have a bit more tension than the 1,3,5,7 and they typically want to resolve to the next closest chord tone, which is exactly what Jerry does in his solo.

What are they thinking?

And here’s where the eternal question comes up – are these musicians consciously thinking about these concepts in the moment?

Chances are, particularly in the case of giants like Dexter Gordon and Jerry Garcia they’re not thinking in such concrete ways when they are improvising.

BUT they have a deep, masterful command of all of these tones over different chords.

Just like a painter can mix colors, or utilize shades to evoke a feeling, master improvisers use tools like chords tones and extensions to tell a story, since each one has a different tone color.

These tools, combined with imagination of whoever uses them is what gives us meaningful melodies that make up solos like these.

What we’re doing here, is just giving labels to these colors, but rather than using visual colors such as red and blue, we give them names like the root, or the fifth, or the 13th.

Guide Tones

In the same excerpt, we notice that Garcia connects the b7th of G7 to the third of C, giving us a smooth transition from chord to chord.

We also see Dexter connecting the b7th of F to the third of Bb.

Jazz improvisers love to focus on Guide Tones, which are tones that capture the very essence of the chord. In jazz and popular music, we often see the 3rds and 7ths acting as these guide tones.

For example, lets look at the first few chords in Society Red, a very common blues form in jazz.

If we just take the 3rd and 7th of each chord, we can capture the entire essence of the progression with only two notes per chord.

This is why connecting the 3rd of one chord, to the 7th of another (or vice versa) is a very common approach in improvisation, because it effectively and smoothly addresses the harmony (the chords that the musicians play around them) in a colorful way.

Both enclosures and chromatic lines are ways of incorporating passing tones into improvisations. These are methods where you can pass through or around tones outside of our scale to add color, excitement and emotion.

Chromaticism

Finally, we see another hallmark of Jazz in Jerry’s solo.

Here, Jerry connects the third of G, to the fifth of G chromatically, in a lick that sounds almost stereotypically jazzy.

We see that that Dexter similarly connects the major 7th of Bb to the fifth the second bar of his solo.

Chromaticism is the approach of playing in half steps, which are the smallest functional units that western music is founded upon. The keys on a keyboard are spaced by half steps, just as the frets on a guitar are spaced by half steps.

So, was Jerry a jazz improviser?

I think if he had devoted his life to playing traditional jazz, he would have worked hard and hustled enough to make a career out of it.

Who knows, perhaps in an alternate universe, Jerry spent his days in the 60s playing hard bop, or in the 70s playing showtunes, or in the 80s with a latin jazz band…

Leave A Comment