Ween performed Roses are Free three times in the summer of 1997, until Phish covered the song in Rochester, New York later that winter.

Dean and Gene were initially so disgusted, that they shelved the song for over two years.

But on April 3rd, 1998 Phish performed a groundbreaking 27 minute version of Roses Are Free to a sold out audience in Nassau Coliseum.

Hi I’m Amar Sastry and welcome to Anatomy of a Jam. This is the Island Tour Roses.

The worlds of Ween and Phish began colliding in the early 90s, when Phish teased Push Th’ Lil Daises at the historic Providence Performing Arts center in February of 1993.

At first glance, it seems that these two bands could not be more different.

With Ween embracing a purely punk ethos – their middle finger squarely planted on society’s face.

And Phish, who earned generations of fans that traveled in the world’s largest hedonistic circus.

But even from the beginning, there were a striking number of similarities between the two bands.

Both got their start when two friends, who met in the eighth grade, began hanging out and writing and recording original music on multitrack cassette tape machines.

Both grew up less than 20 miles from one another in the northeastern US.

Both slogged it out in local bar scenes, toured the nation thanks to word of mouth, and graduated to bigger venues until they were signed by Elektra Records.

In an interview with Phishbase, Sue Drew, the A&R rep who signed Phish to Elektra in 1991, recounted battling Phish’s reluctance to sell out or get in bed with a corporation:

“Frankly I don’t think [Phish] had any interest in signing to a major [label] but at some point they came back to New York. At Elektra Records we had a wonderful secret in our record cabinet. In those days we used to keep copies of all the CDs that we had released previously. We’d have five to ten copies of everything and it was an incredibly impressive roster through the years from Elektra’s inception until that time. So I brought them into the record cabinet, opened it up and their eyes just popped out because you know everything from the Eagles to Tim Buckley to Motley Crew and Metallica and The Pixies, I mean, it was just an amazing array of talent historically speaking and current day. And I think at that point, when they opened that up and saw that, they might have reconsidered and thought yeah I want to be part of this.”

In Hank Shteamer’s Chocolate & Cheese (essential reading for any Ween fan) Trey Anastasio directly credits Sue Drew and Elektra for turning him onto Ween. Trey said:

“When we got signed to Elektra in ’92 or ’93, Sue Drew, our A&R person at the time gave me a copy of Pure Guava. Ween had also just been signed to the label.I loved that record from the second I put it on, and I remember playing it with my wife (then my girlfriend) in my room in Winooksi, and the two of us just cracking up.That was my first encounter with Ween. I thought they were incredible…

…then I discovered God Ween Satan and went around the house singing ‘Squelch The Weasel’ and ‘El Camino’ for weeks. I was hooked.The interesting thing to me about Chocolate and Cheese is that it has some songs on it that really showcase the depth of their songwriting talent.”

Ween was recruited to Elektra by the visionary VP Steve Ralbovsky, who during his career has also signed Soundgarden, Nanci Griffith, Anthrax, The Breeders, Kings of Leon, My Morning Jacket, Ray LaMontagne, The Kills, the Strokes, among others.

In an interview with Magnet Magazine, Dean Ween recounted his sense of bewilderment and joy of joining the major label:

“One day, a box of Pure Guava discs shows up from Elektra, and I started crying, because I was a music junkie and now we were on the same label as The Doors. Here was this record that we recorded in our apartment for not even two dollars — we didn’t even buy new tape, just taped over demo tapes bands gave us on the road — and it’s on Elektra.”

Roses are Free is the sixth song on Ween’s Chocolate and Cheese, which was the band’s fourth album, but their first one recorded in a professional studio with a real live human drummer.

The album’s cover, which seems inspired by the Commodore’s All the Great Hits, appears a subversive, sarcastic symbol of the band’s ascent to living life under a major label.

As Hank Shteamer, who called Ween’s album cover an over-the-top sight gag, wrote in Chocolate and Cheese:

“There’s nothing extraordinary about adorning one’s record with a barely concealed depiction of female nudity. But rarely has erotic album art seemed so at odds with the music inside it as it does in the case of Chocolate and Cheese. Contemplating the photos of the boognish-belt-clad model, one thinks of countless other borderline-pornographic album covers: Roxy Music’s Country Life, the Black Crowe’s Amorica…the cars’ Candy-O, or various 70’s funk titles by the Ohio players and similar acts.

But while all these releases explore themes of lust and romance with varying degrees of sleaze, there’s barely a mention of Sex to be found on Chocolate and Cheese…the content of the album seems much more in keeping with the disheveled weirdos audiences encountered in the “Push th’ Little Daises” video rather than any sort of oversexed rock stars…Perhaps the band was even satirizing their own sonic upgrade, complementing their slicked up sound with an image that could superficially read as a desperate attempt to conform to the rock mainstream”

Exploring Roses

Roses are Free has a fairly typical verse-verse-chorus pop song structure, with an intro and guitar solo thrown in for good measure.

In an interview with Jambase, Dean explained the inspiration behind the joyful, off kilter vibe of Roses are Free.

“Aaron wrote this song and recorded it in his apartment in Stockton, NJ during the very fertile writing period preceding Chocolate and Cheese. There was no bass on it. I immediately fell in love with the song and thought it was the closest thing we’d ever recorded to truly emulate Prince, who is our musical hero. The demo was on four tracks with two vocals, drum machine and keyboard. I heard it as being symphonic. I think it’s ironic that as many times as we’ve worn our Prince inspiration on our sleeves that no one ever picked up the obvious, massive Prince influence of the song.”

Phish are also deeply inspired by Prince, having performed 1999 and Purple Pain throughout their career, and having publicly professed their love for his music in print. Trey recently told Rolling Stone about an extravagant night in November 1996, when Phish was in town to play an arena in Minneapolis, and was invited to Prince’s secretive Paisley Park compound for a party to celebrate the singer’s release of Emancipation.

“We were kind of standing in the corner,” Anastasio says. “One thing I remember is [Prince] didn’t serve cocktails, so in lieu of cocktails he served little Captain Crunch cereal boxes. I thought that was the coolest thing.”

Trey mentioned that the highlight of the night was standing a few feet away watching the purple-clad legend and his band performing through plexiglass gear. He continues:

“[Prince] was such a great guitar player, but people don’t point out he was a great rhythm guitar player. The band was playing this funky stuff. He had a woman singing with him, a kind of gospel singer, and she stepped out and started killing it. He stepped back, and I remember thinking that everybody tries to play like James Brown’s rhythm guitar player. Jammy guys do it a lot, and they all get it wrong, myself included. He was playing the most badass little rhythms with the drummer as soon as he got out of the spotlight. I was so fascinated by what he was playing. That’s when I noticed what a great guitar player he was.”

Anatomy of the Island Tour Roses

Roses are Free opened Phish’s second set on April 3rd, 1998. From the band’s body language, it seems that Trey called Roses, meaning that it wasn’t necessarily planned or on the setlist. In the early days of Phish, setlists were often carefully crafted before a show but that was no longer the case by the mid 90’s, as we see here.

We see him start the song, but the rest of the band doesn’t immediately catch onto what he’s playing. It takes a minute for Fish, Page, and Mike to get on board.

The performance gets off to a rocky start. The band seems unsure from the very beginning, leaving a small but noticeable trail of vocal mishaps and missed changes at nearly every turn.

But with Phish, sloppy playing would often act as a catalyst – a transformative kick in the ass that pushed the band to play even tighter as the song ran its course. You can even see Trey internally chastise himself for missing the easy chromatic walkup during the chorus.

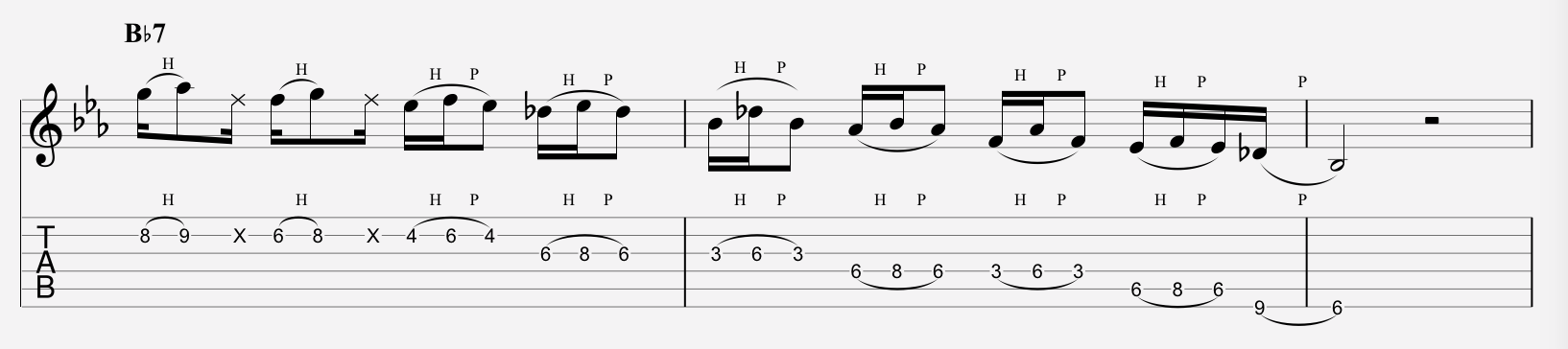

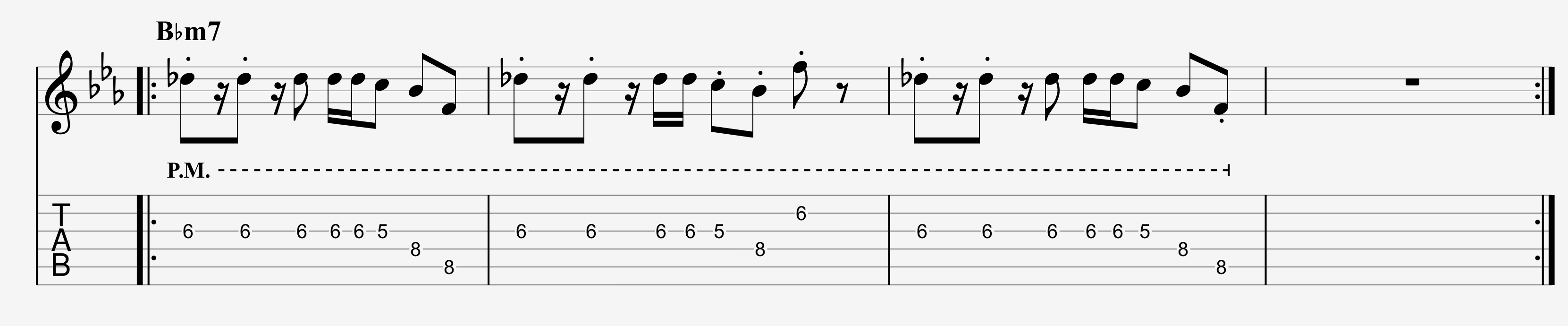

We see the moment that Trey decides that they are going to jam the song, as he pummels 16th note Bb power chords with downstrokes through the song’s typical ending spot near the 5:45 mark.

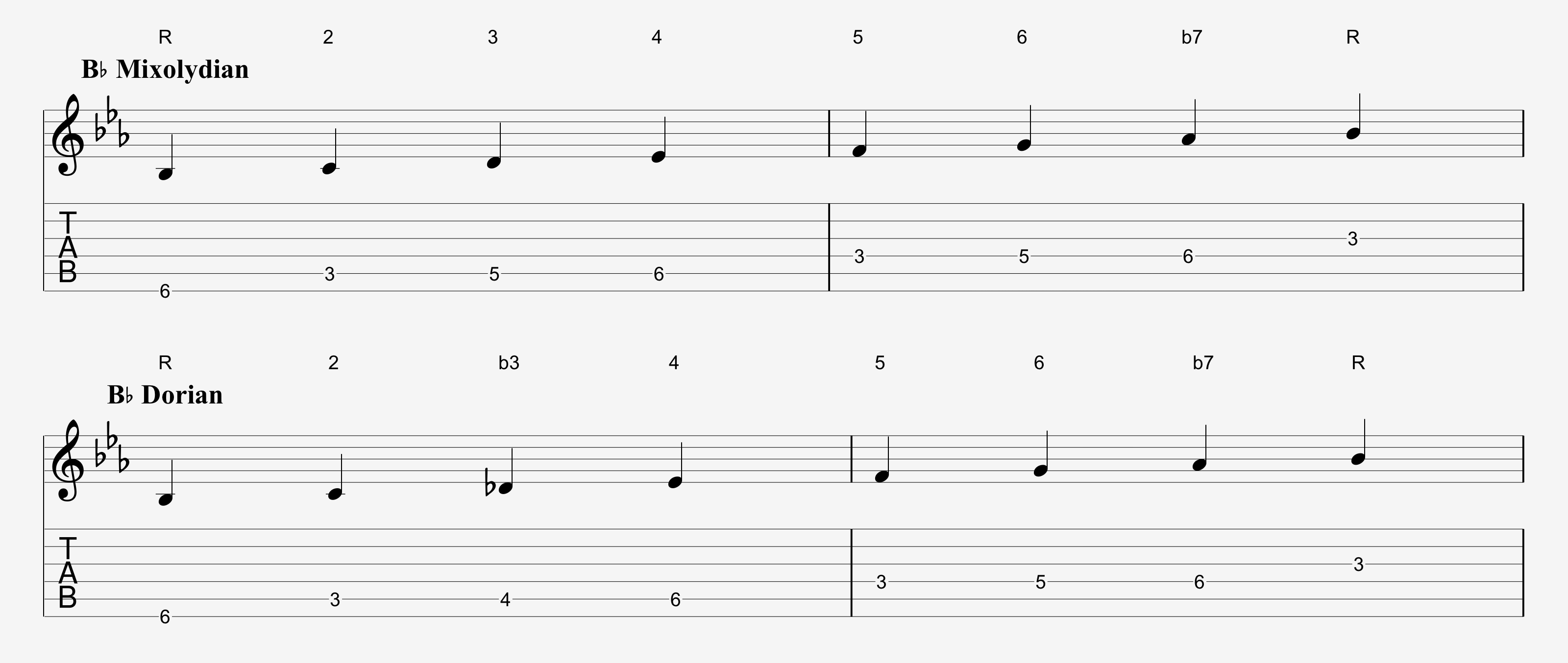

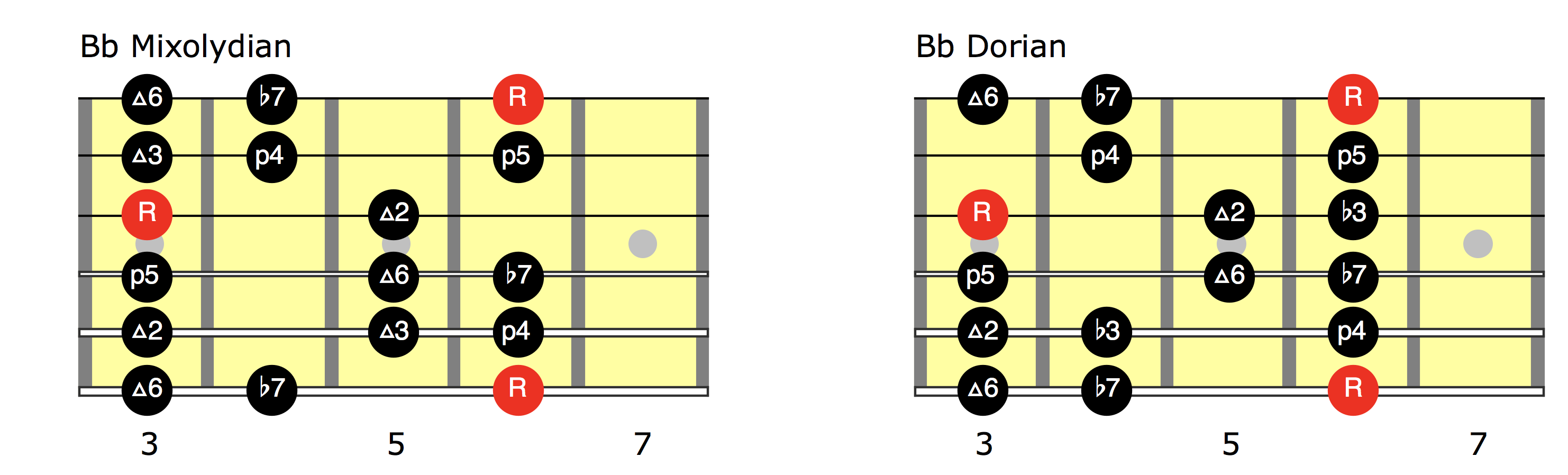

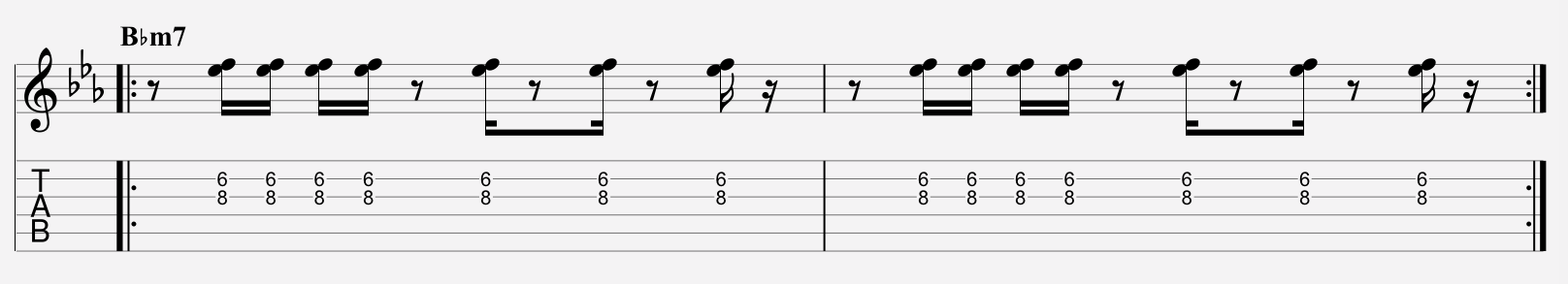

The “whats going to happen” feeling is palpable both on stage and in the stands as Phish rolls through Trey’s power chords at the end of the song. The the decision to take roses out for a spin is cemented by an impromptu vocal jam as Trey simultaneously guides the band into Bb mixolydian territory.

At the 7:30 mark, trey loops a small piece of ambient feedback that looms throughout the jam. This is a subtle move with big implications – the note that he loops is the note Bb, the root of the jam, suggesting that he wants to dive in modally and not leave the harmonic vicinity for a little while anyways.

Page also switches to the prototypically funky Clavinet at this time, while Trey clicks on his wah pedal and goes into full rhythm guitar mode. Both of these pieces of gear are quintessential sounds for funk, having been employed by countless pioneers of the genre like Parliament/Funkadelic, Stevie wonder, Herbie Hancock, James Brown, and of course, Prince.

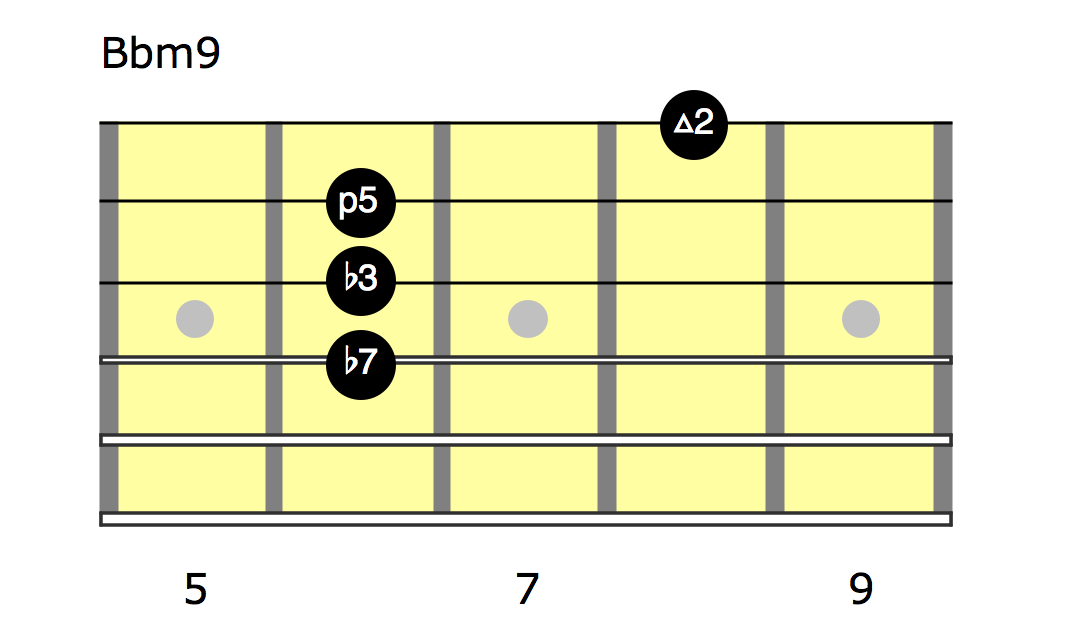

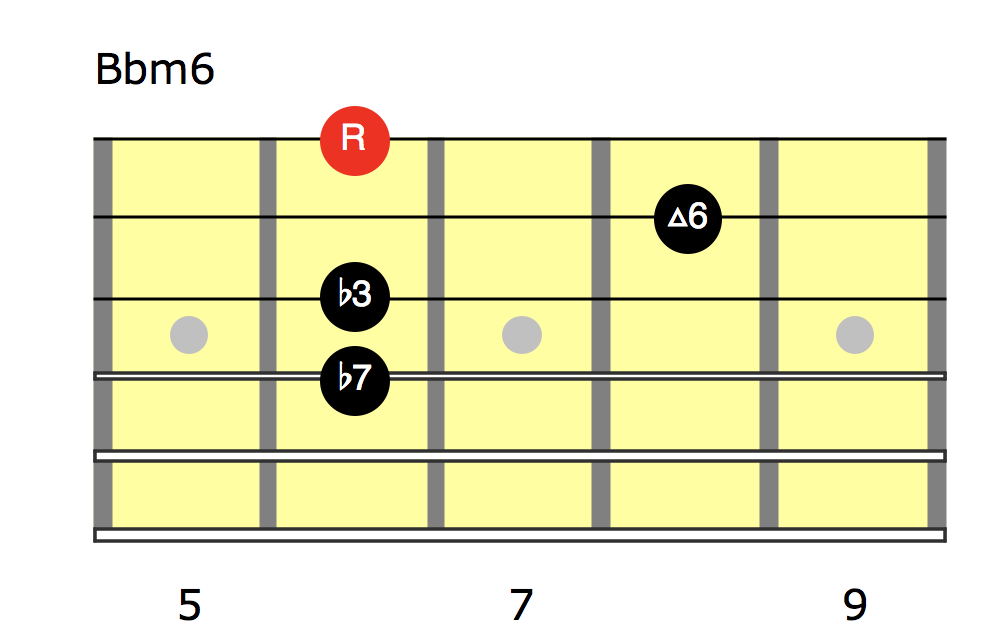

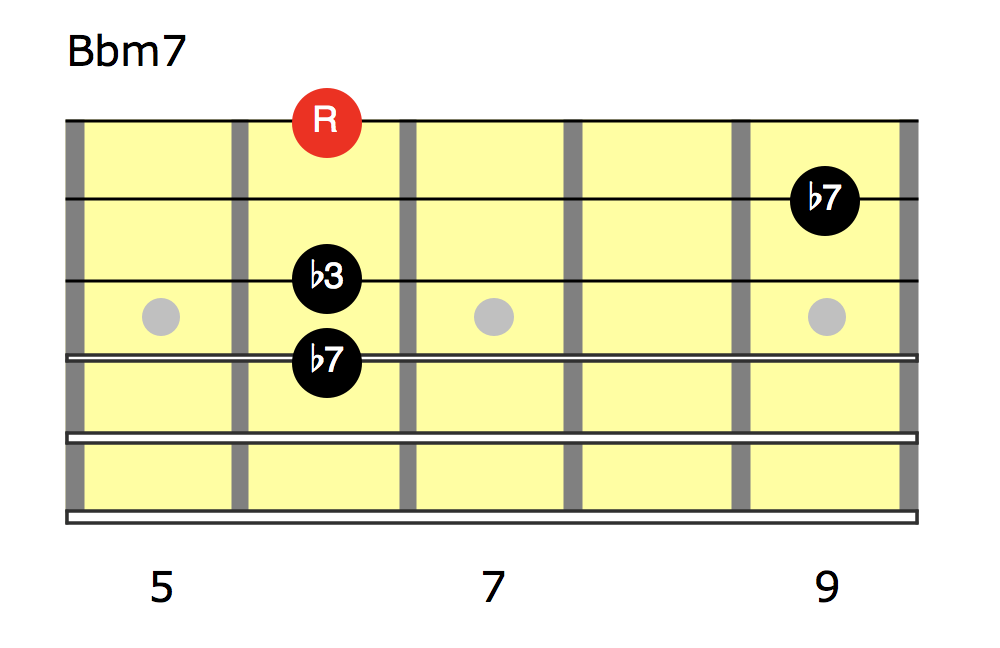

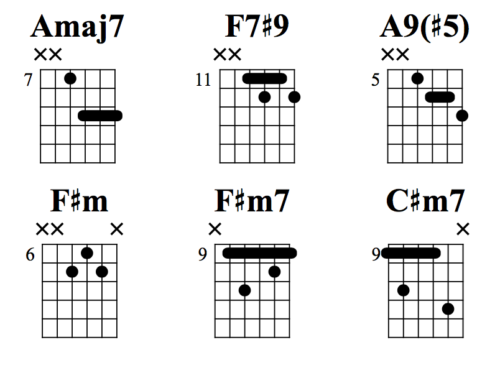

Trey even uses many of Prince’s favorite guitar voicings and rhythms during this jam, including the m7, m6, and the m9 – the holy trinity of minor funk chords.

Have a Cow, Man

As Trey told biographer Richard Gehr in The Phish Book:

“What we’re doing now is really more about groove than funk. Good funk, real funk, is not played by four white guys from Vermont. If anything, you could call what we’re doing cow funk or something.”

Trey being the self-effacing musciologist that he is, may have also been making an allusion to Cowpunk, the country-punk blend that eventually gave birth to both Alt-country and Psychobilly.

But Cow funk, which began to take hold of the band in 1997, is notable since each instrument is relegated to a rhythmic role.

The band collectively abandons traditional conventions of soloing and rather focuses on establishing an improvised hypnotic dance groove, without having any one member take the lead.

This may seem like modern day jamband 101 but back in the mid-to-late 90s for a rock band touring the arena circuit, it was completely groundbreaking.

Not all Phish fans enjoyed this style of jamming, which many die hards described as being neutered, directionless, and lazy. Especially coming off the heels of the fertile years of 1992-1996, where the average Phish improvisation was a mindbending rollercoaster of virtuosity and effortless dynamics.

But by 1998, the band had already had about a year of experimenting with the Cow Funk style and started to break new ground again, as we’ll soon see.

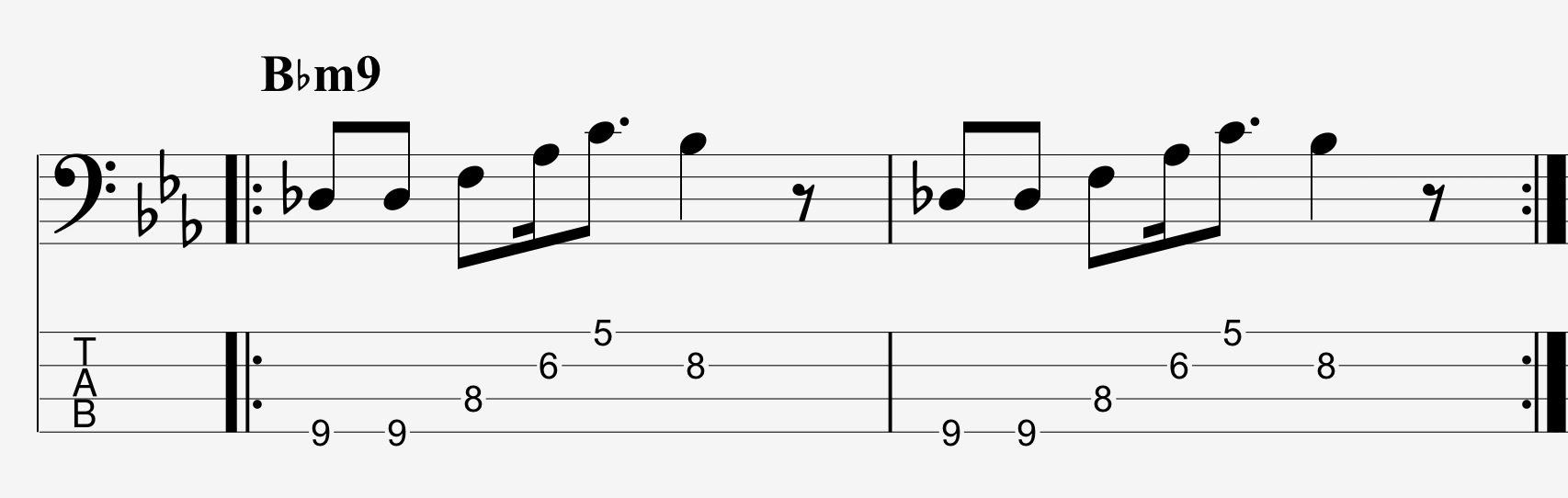

At 8:10, we have more vocal jamming and at 9:17 we see Mike going out on a limb and trying to take the lead.

At 11:52, Page improvises a beautifully funky descending lick where he mixes Bb dorian and Bb minor pentatonic which ripples inspiration throughout the band.

Moving from Mixolydian to Dorian

Experienced musicians understand that improvisation is a conversation, and that to really connect with the audience and your band members, you have to listen more than you play, which is what each member of Phish is expertly doing in this jam.

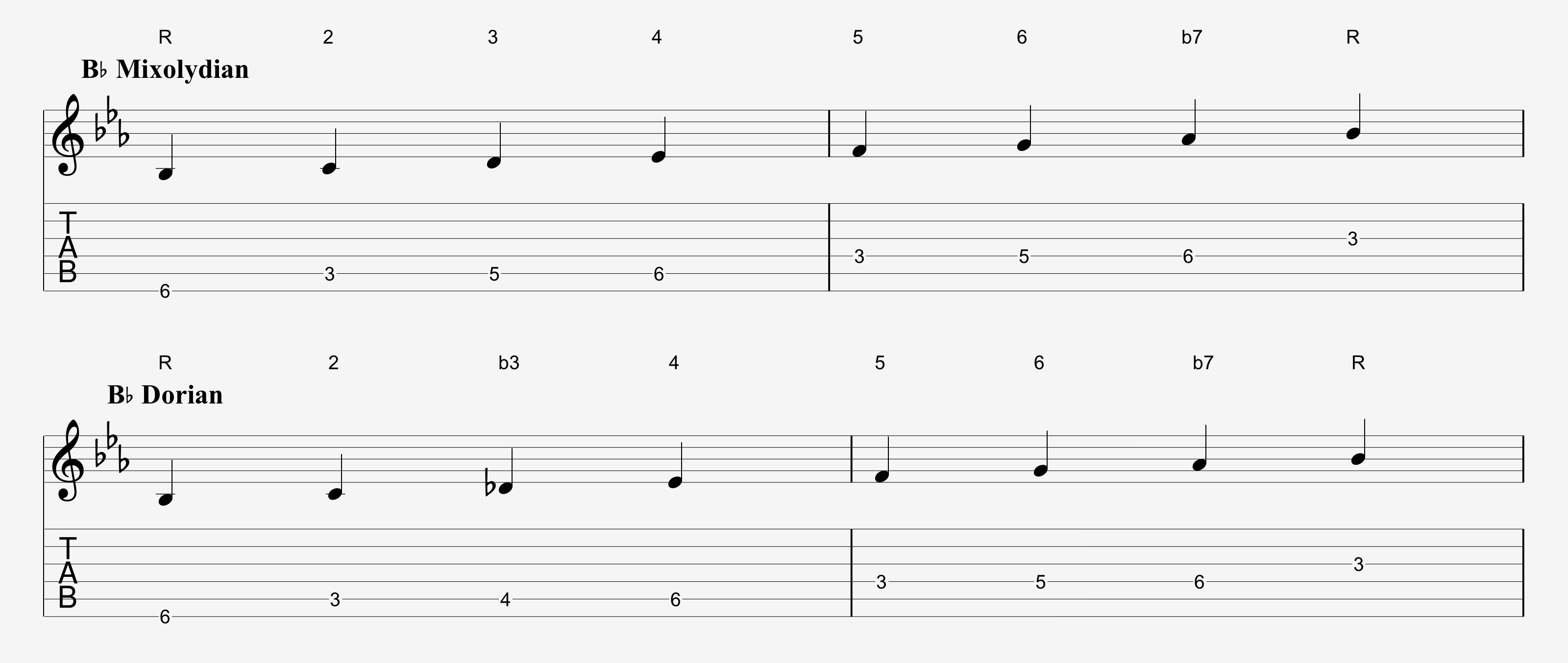

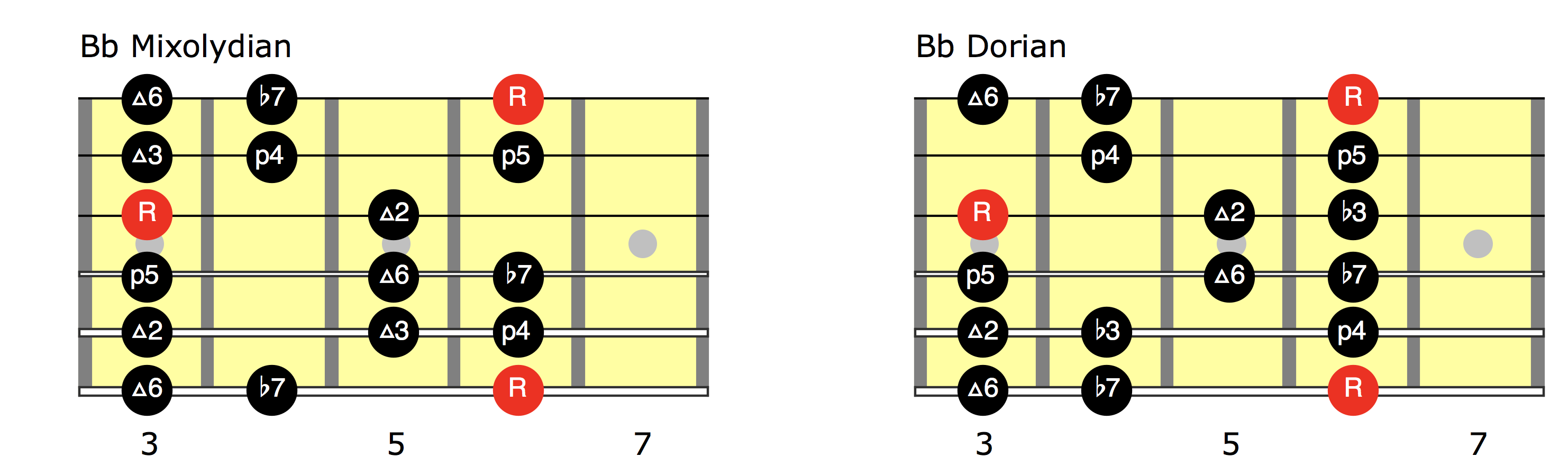

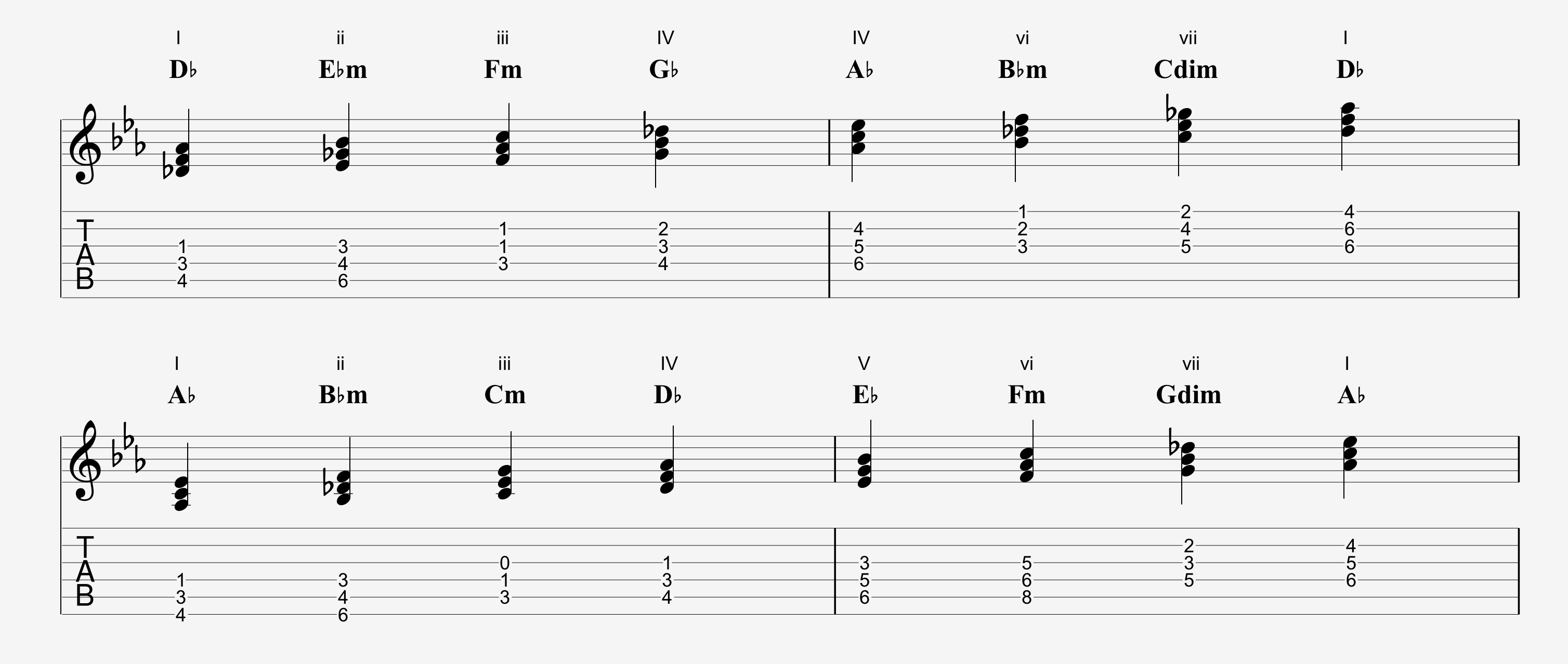

In the beginning of this jam, the band was largely centered around Bb mixolydian and a Bb7 tonality. That just means that they’re all loosely improvising within that mode. But Trey started playing Bbm voicings, which Page uses as a backdrop to improvise in Bb dorian and Bb minor pentatonic.

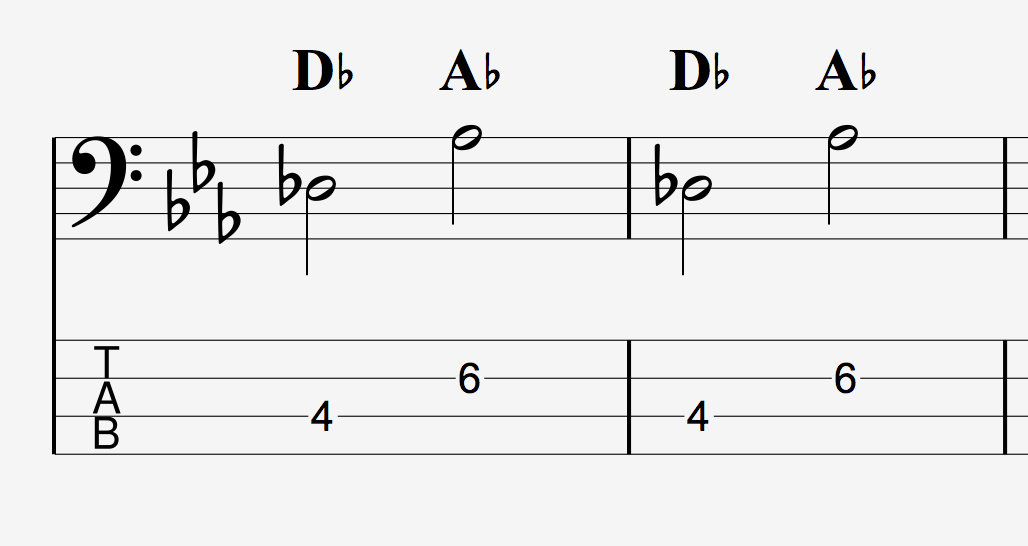

At 12:43, Mike takes that inspiration from page and trey, and distinctly steers the jam from a Bb mixolydian tonality to a Bb minor tonality.

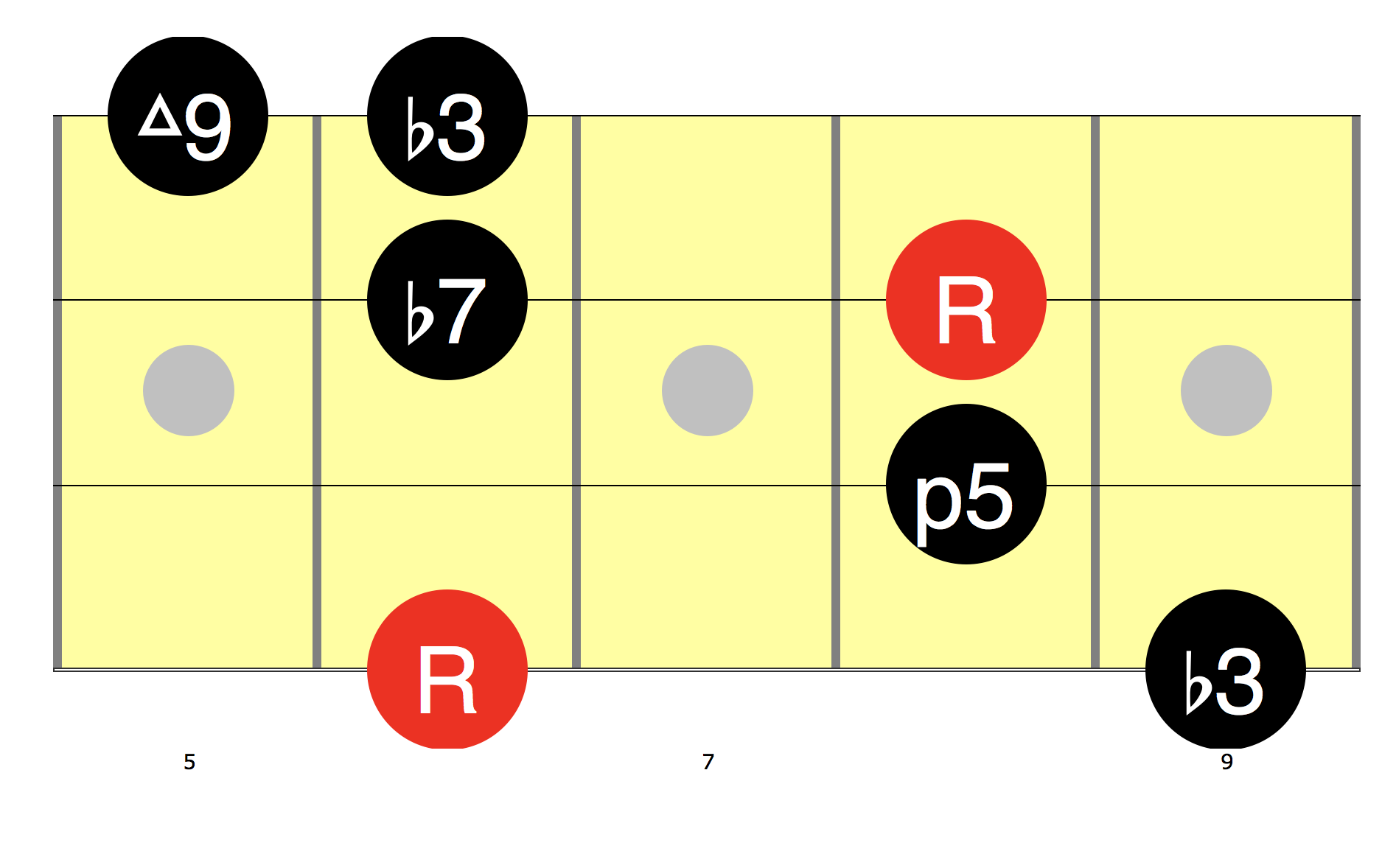

He accomplishes this by repeating a syncopated Bbm9 arpeggio ascending up from the 3rd. Mike accents the minor 3rd, the note Db on the one, which is the first beat of each measure.

The third degree of any chord or scale is crucial in determining the tonality of a chord.

Major chords have a major third, minor chords have a minor third.

In addition, the only difference between the first mode of this jam, Bb mixolydan, and Bb dorian, is that dorian has a minor third.

Since Page’s and Trey’s improvising are clearly defining the root, Bb, this frees Mike up to accent the minor third, effectively and concretely pushing the jam’s harmony into this new Bbm tonality.

The third degree of any chord or scale is crucial in determining the tonality of a chord.

Major chords have a major third, minor chords have a minor third.

In addition, the only difference between the first mode of this jam, Bb mixolydan, and Bb dorian, is that dorian has a minor third.

Since Page’s and Trey’s improvising are clearly defining the root, Bb, this frees Mike up to accent the minor third, effectively and concretely pushing the jam’s harmony into this new Bbm tonality.

Don’t Start/Stop ‘Till You Get Enough

Trey can hear both Mike and Page taking up more space and starts paring down his rhythm voicings, from four note chords, to three note chords, down to a beautifully economic two note voicing.

It’s clear that the band was focusing on their sense of groove and patience during this period, when At 13:13, Trey finally starts playing single notes. It’s taken a full seven and a half minutes from the beginning of the jam until he plays something a guitar solo, which is an eternity in the Phish world.

But instead of playing a typical improvised solo, we see him thinking rhythmically again using repeating phrases as the other members percolate and shift their own repeated phrases underneath him.

At 13:47, Trey shortens his motif and plants the seed of a start/stop jam by leaving the fourth bar empty, allowing his band mates to fill them in.

Great improvisers often think in 4, 8, and 16 bar phrases, and we can hear the band collectively doing this. They think, play, and feel in four bar phrases as a unit, thanks to their time spent absorbing and studying the great musicians that came before them, as well as the multitude of improvisation exercises they practiced for years off stage.

At 16:05, Fishman briefly improvises a new afro-cuban beat inspired by a 3-2 son clave. This new syncopated beat is jagged compared to the smoother straight funk feel that he was playing and served as a major pattern interruptor for the rest of the band since it seemed to snap them out of their trance.

This whole time, we could still hear the band collectively improvising in four bar phrases, until they all leave the whole fourth bar empty, resulting in a start/stop jam. Given the crowd’s response, it was the musical equivalent of hitting a home run. We see that, what seemed like telepathy, is just the fruit of pure, egoless listening.

Let’s listen to the rhythmic space each member occupies in the minute leading up to the start/stop. It’s Trey that has been leaving the fourth bar empty on his motifs, and one by one, each member catches on and mimics his use of space.

Modulation Station

The jam takes another major turn around 17:10 when Trey abandons his 16th note funk rhythm guitar work and begins experimenting with sparse triads. They collectively explore and wander until the water starts flowing through the hose at 18:22 when trey spontaneously composes a beautiful, mysterious theme. The rest of the band can hear that he’s in Bb dorian and they follow and support him in kind, until a moment of true telepathy happens.

Page and Trey simultaneously land on the fifth of Bb, which is the note F at 19:15, Once that happens, we can feel the sound coalesce like two massive magnets spinning around each other and smashing together. Page and Trey run with with moment, giving us a spontaneous modulation to the key of F. Trey quickly suggests F Dorian and the rest of the band, like the true brothers they are, are right there to support him in F Dorian.

We can feel the energy in the room start to expand and lift as they drive this into a stunning crescendo that sounds like Keith Jarrett sitting in with Sigur Ros. Fishman and Mike rhythmically weave in and out of time as Trey and Page shower the audience with elegant, criss crossing melodies.

Mike propels the band into a new section by subtly playing Db and Ab, implying Db major and Ab major chords.

These three chords, Db, Ab, and Fm can either be viewed as living in the key of Db, or in the key of Ab. So the band is driven to choose between one of these two keys to modulate to.

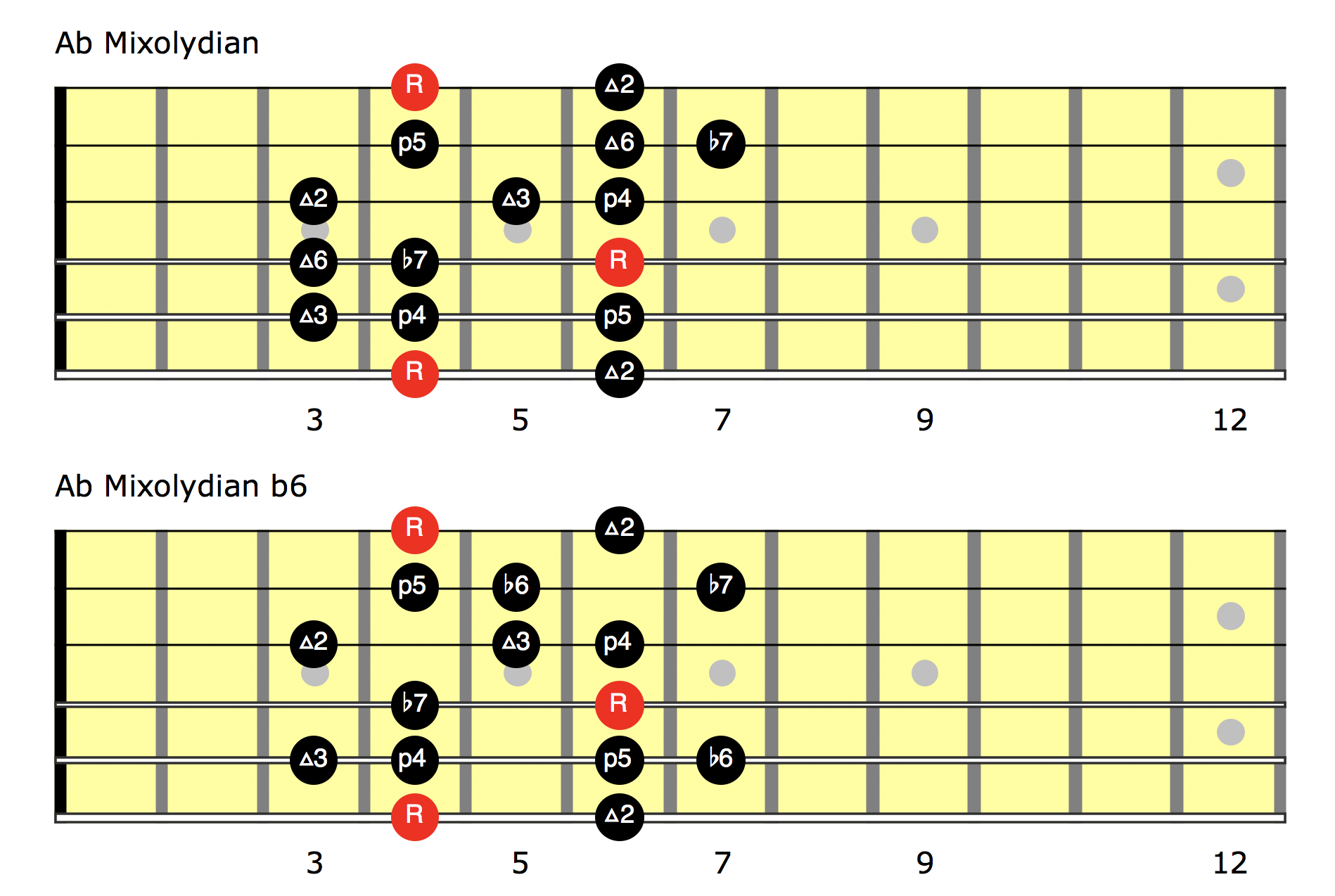

Page suggests that they modulate to Db by playing Db major chords. But Trey entered with a melody based in Ab mixolydian and the band falls in line and supports him. Now Db major and Ab mixolydian have the same notes. But the home base of Db major is Db, and the home base of Ab mixolydian is Ab. The band can hear trey hinting at Ab Mixoydian based on the chord tones he stresses, and they follow suit by adding supporting harmony and cycling melodies in Ab major.

Trey also creates another change in the jam, but this time, rhythmically- his melodic line is loosely based in a 7/8 time signature, and the entire band hears that and lightens their grip on the more standard 4/4 time signature that the jam has been based on.

The band collectively weaves in and out of time, which gives us that beautiful, ethereal feeling like we’re floating in space. But the fact that they’re all slowly building tension in Ab mixolydian is what gives us that grounding feeling of coalescence.

Trey improvises leads that are both somehow fierce and blistering, yet soothing. He’s improvising in mostly Ab mixolydian and throws in a splash of Ab Mixlodyan b6 which is the 5th mode of Db Melodic Minor for some added tension.

The entire band decides to collectively amplify the tension by playing completely freely – that is, ignoring the key and in this case ignoring any semblance of a pulse or time signature.

We watch in awe as they joyfully tear down the castle they’ve spent he last 20 minutes carefully building. In a fit of controlled chaos, the wheels are falling off and we love it. Kuroda assumes the band isn’t done yet and that they’re going to take it even further out into space, so he launches the classic mothership effect.

However, he sees Trey walk over to Page and call the next song, so he respectfully shuts off the effect and gives them a standard wash so they can communicate a little bit easier. The band winds down Roses are Free and segues into Piper.

This Is the End

Ween and Phish have been heroes of mine for over 20 years. Both bands showed me that it’s ok to be different, it’s ok to be weird, it’s ok to be unapologetically yourself. But that has to come with an uncompromising commitment to sharpen your craft, break your own perceived boundaries, and make your voice heard even if, at first, no one is paying attention. They gave me the gift of learning one of the most important lessons I’ve ever learned. And that’s the fact that courage isn’t the lack of feeling fear. True courage involves experiencing fear, and acting anyway. So go out there and make something happen. And make sure it’s f*cking beautiful.

Leave A Comment