So many artists spend their lives toiling on the road and in the studio, working their fingers to the bone and leaving their personal lives in ruin as they become a victim of their own success. That’s the reason why Phish, one of the hardest working acts of our time, took an eight hundred and fifteen day break at the turn of the century. The band toured relentlessly from their inception in 1983 until October 7, 2000, where they embarked on a hiatus that was gut-wrenching for most, if not all, of their hard core fans.

As Neil Strauss wrote on October 10th of 2000:

“Phish has not broken up for good, the band’s management says. But it is breaking up for a while, leaving a gaping hole in the lives of the thousands of fans who follow the band from city to city. No concerts are booked, no albums are scheduled, and band members plan to go their separate ways. ”The plan,” said the group’s spokeswoman, ”is that there is no plan.”

When Phish announced their return in late 2002, fans didn’t know what to expect. As excited as we were, there was a fear that they may have lost something in the hiatus. But on February 28, 2003, at the tail end of their first full tour as a freshly reunited band, Phish performed a extraordinary concert in New York that included an awe-inspiring rendition of one of their most-loved tunes. Hi, my name is Amar and welcome to Anatomy of a Jam. This is the Nassau Tweezer.

Bred From Humble Beginnings

The first performance of the song, which back in its early days, was known as “Tweezer so cold”, happened on March 28, 1990 at Denison University in Ohio. Tweezer was a collaboration between all four members, a spontaneous riff rock jam that took shape during soundchecks, and evolved along with the band and its diehard followers. Trey dedicated this performance to the Beta Intramural Hockey Team at Denison University, as a solace for watching their season go down in the tubes that same day.

Tweezer is a frenetic blues-based tune that combines techniques drawn from both hair metal and funk. It has been a fan favorite for nearly thirty years, as well as a vehicle for some of the bands most fiercely innovative improvisations.

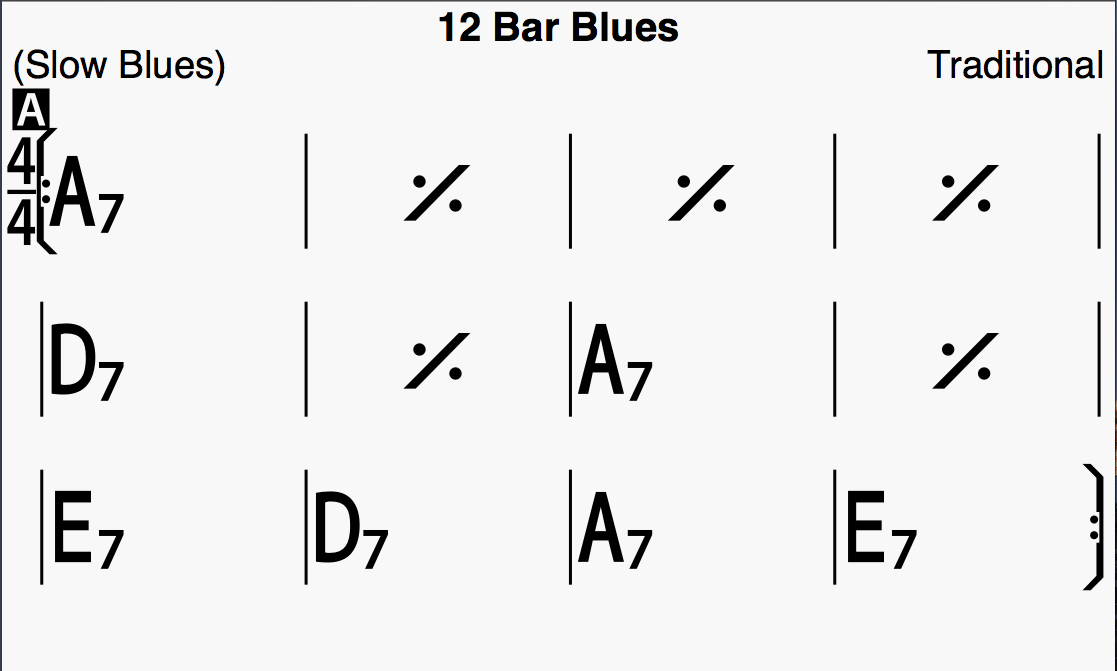

Here, we have a classic 12 bar blues in A. We see that we have three groups of four bars that comprise the entire form. The form being this set of chords, played from beginning to end and repeated for the duration of the song.

One of my favorite descriptions of the 12 bar form comes from Miche Braden:

“A blues, especially if you deal with a 12-bar [blues], is set up like a joke. You repeat the line twice and then you’ve got the punchline at the end.”

Let’s take a look at very literal example of this idea, here’s one of Bessie Smith’s verses from Empty Bed Blues:

He used to cook up my cabbage, and make it nice and hot

He used to cook up my cabbage, and make it nice and hot

When he put the bacon in, well, he overflowed my pot

Miche goes on:

“Its a happy music, it truly is. It’s just that some of the subject matter of the Blues sometimes had that sad feeling, but truly, it is not a sad music.”

The Wackiest 32 Bar Blues You’ll Ever Hear?

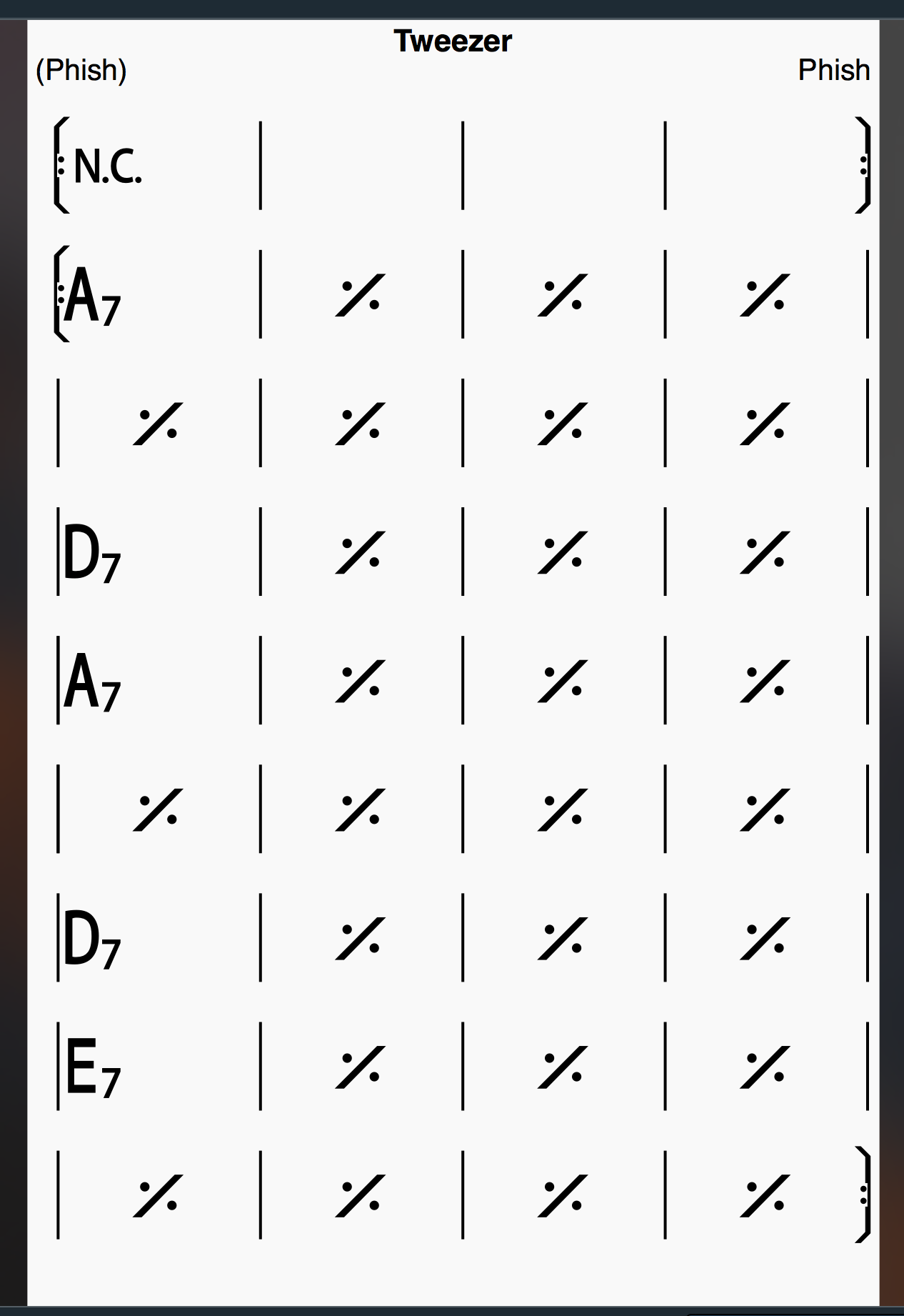

Tweezer, which easily is on the happier side of the spectrum, takes a 32 bar blues form.

Here, we have eight bars of the I chord, four of the IV chord, and that section repeats twice. Then we finally get to eight bars of the V chord, which acts as that lyrical and stylistic punchline.

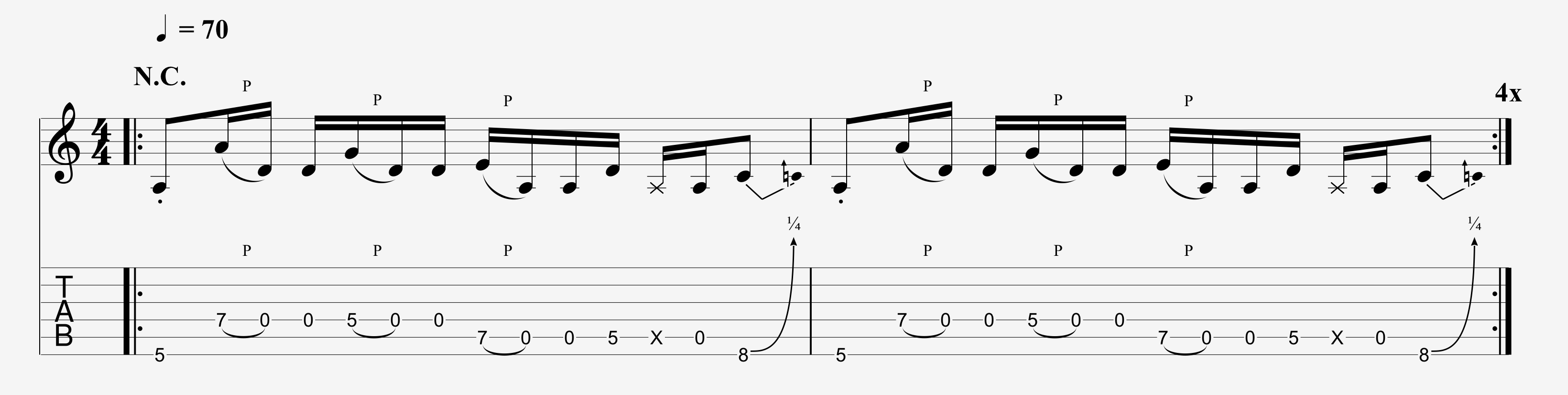

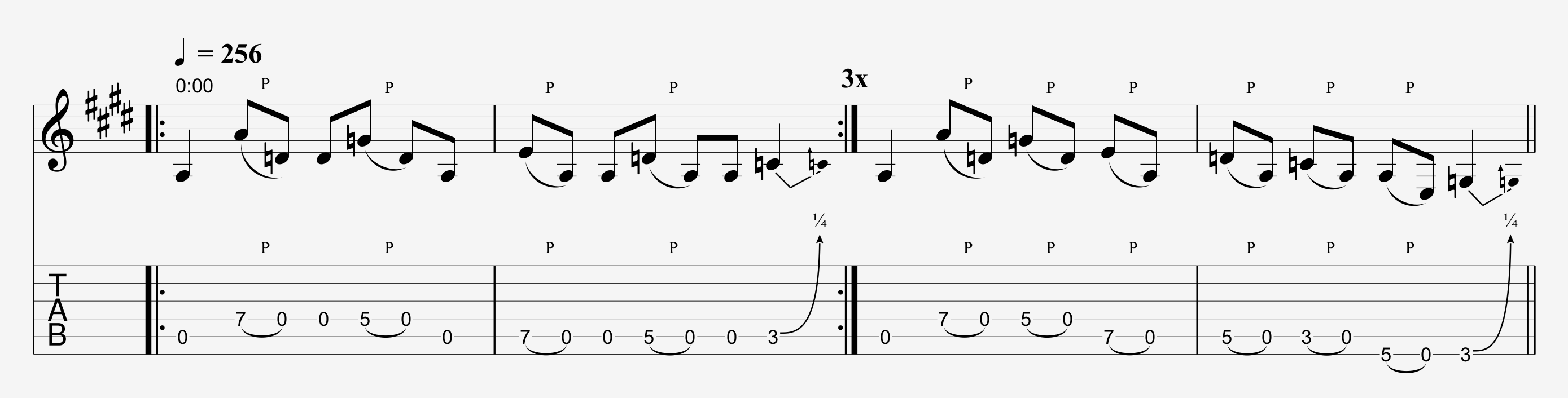

The song starts with Trey Anastasio’s iconic guitar intro.

Some classic rock fans claim that Trey was inspired to write the riff after hearing Time Out by Joe Walsh

Yet Pantera fans are adamant that Anastasio ripped the lick off of Killers.

The Tweezer guitar riff uses all of the notes of the A minor pentatonic scale. “Pent” meaning five and “tonic” meaning tones, or notes. This five note scale in the key of A, has the notes A C D E G.

The pentatonic scale has been found in every type of music across the globe. As Howard Goodall said in the BBC documentary, How Music Works:

“Every music system in the world shares these 5 notes in common. They’re so fundamental composed or performed anywhere on the planet, that it seems, like our instinct for language, that they were pre installed in us when we were born.”

The opening riff is just the scale descending, but Trey leverages two open strings of the guitar. As luck would have it, these open string notes are already within the A minor scale, so the riff fits neatly on the guitar.

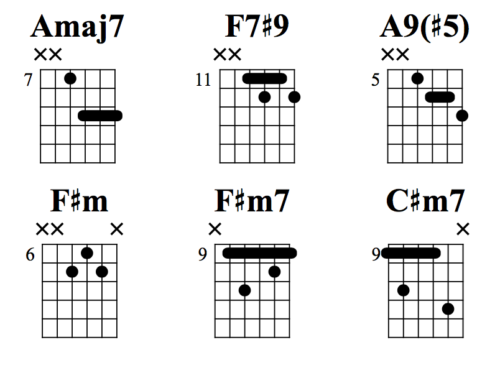

After 4-8 repetitions of the guitar intro, the rest of the band comes in. Fish drops in with the song’s signature funk beat. Page’s syncopated stabs add an infectious groove underneath Anastasio’s guitar riff. Wynton Marsalis once said that the blues can often be characterized by the mixing of major and minor sounds. Page’s major and dominant chords, played over Anastasio’s minor riff, are what give Tweezer that indelibly bluesy sound.

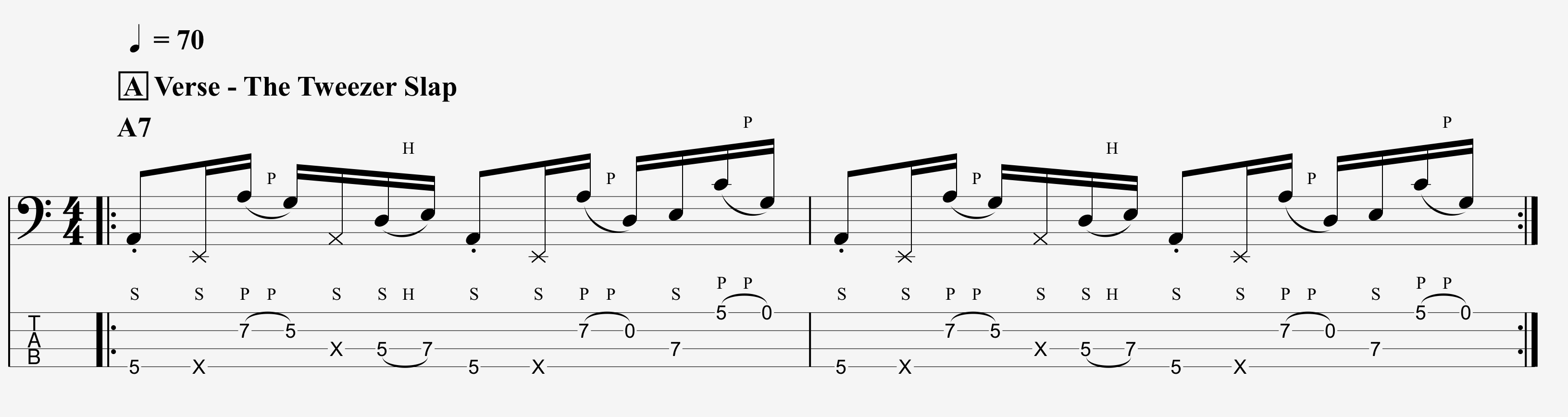

The real hero of this section is Mike Gordon’s aggressively percussive slap bass line.

Slap bass is a technique pioneered by one of the greatest electric bass players of all time, Larry Graham, on Sly and the Family Stone’s Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin).

Graham said that he developed this technique as a child, playing in his mother’s band. For unknown reasons, Ms. Graham had decided to fire the band’s drummer, possibly in an effort to increase the take-home pay of the remaining members.

“I started thumping the strings with my thumb for not having the bass drum, and plucking my finger to make up for not having that backbeat on the snare drum. So it’s kinda like playing the drums on the bass.”

Perhaps a lesser bassist would just pluck this bassline. But Mike’s slap technique adds heaps of attitude.

Mike, like trey, Restricts himself to the notes of the A minor pentatonic scale. The open strings on a 4 string bass also happen to have notes that are already within the A minor pentatonic scale.

Throwing a Heady Nod to the 80’s

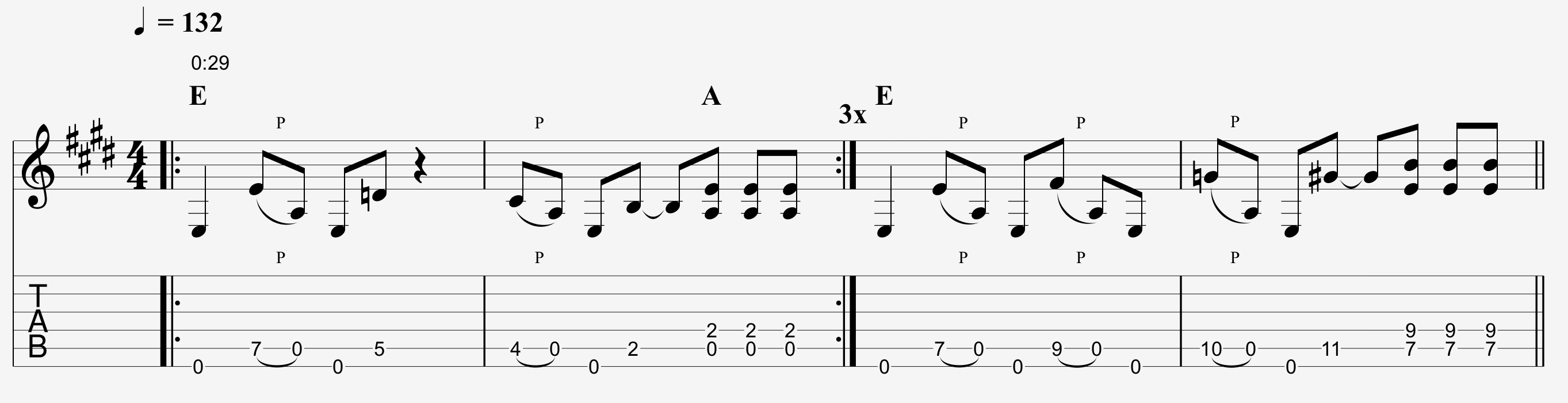

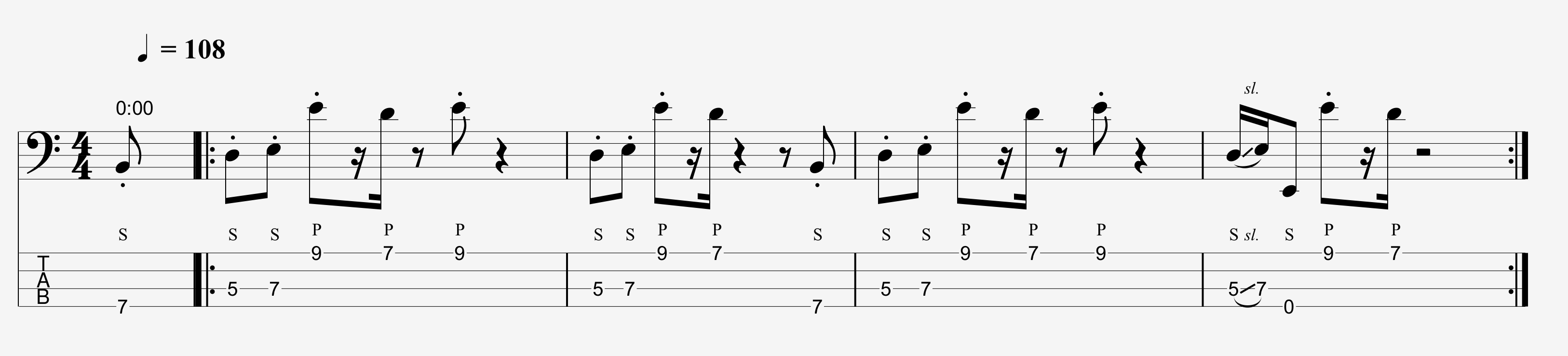

When the band gets into the D7, the IV chord, Mike and Trey take a bit of a stylistic left turn. They don’t actually play chords in the traditional sense, in the way that you’d typically hear in a blues or rock song. Rather, they play a synchronized harmonized lick that spells out a D9 chord.

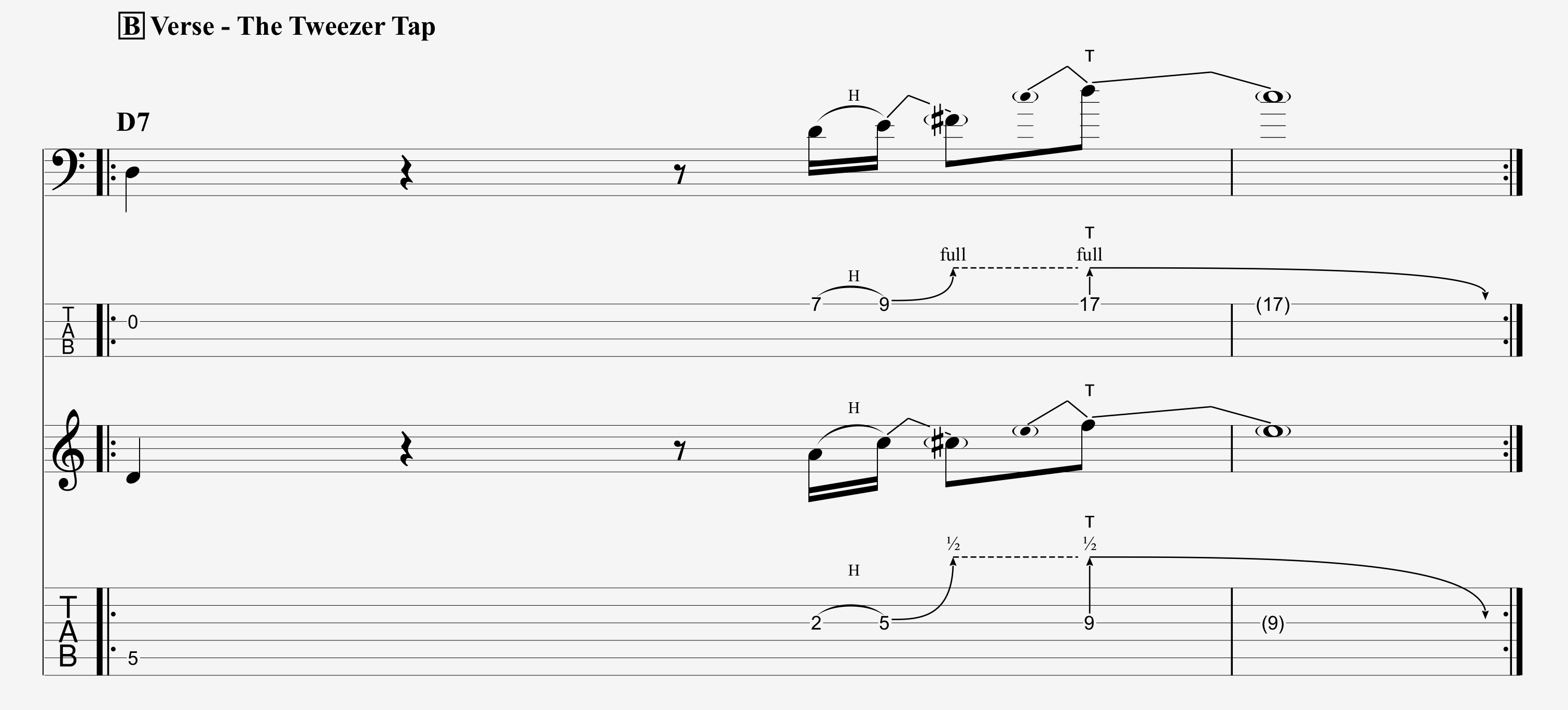

This lick, The Tweezer Tap, gets its name from an advanced lead guitar technique popularized by Eddie Van Halen in the late 70s.

Although Eddie was not the first player to use two handed tapping, he created a phenomenon with his stylistic approach to the technique at the end of Eruption, the first track on Van Halen’s debut release. This approach was so unique that, within a few years, every lead guitar player in spandex was trying to cop it, provided they could even figure it out in the first place. It quickly became one of the defining sounds for the entire genre.

As Trey told Guitar World Magazine in the August 2000 issue about Tweezer:

“At the beginning of the verse section, I play a fretboard tapping lick. First I fret an A note with my index finger, and I hammer on to a c note with my pinkie. The C is bent one half step up to C#, and, while holding the bend, I “tap” the same string behind the 9th fret with the middle finger of my right hand. The bend, which is executed with the left hand, is then released while the “tapped” note is still held. Mike harmonizes this lick with a similar lick on the bass. That’s our nod to the Eighties!”

Coincidentally, Tweezer got its start on the very last night of that decade, on 12/31/89, when the band spontaneously began to compose it during soundcheck that very evening.

The form of Tweezer has stayed fairly consistent over the last few decades. We have our guitar intro, then the form repeats twice. After that, we have a short mini-jam and then the full jam.

Long Island…More Than Just Brooklyn’s Fart Trail

There are few moments in the song, before the jam officially starts, that set the Nassau Tweezer apart from other version played before or since. Two and a half minutes in, we have a massive glow stick war, which is a spontaneous ritual where the audience arcs glowsticks as a sign of celebration and excitement. This might sound pointless to the uninitiated, but a glow stick war has been known to cause an exponential boost in the energy of the room, as evidenced by the crowd’s reaction Thirty seconds later, we have another glow stick war that was even bigger in magnitude than the first. At this point the vibe in the arena was absolutely explosive. But at 4 minutes, disaster strikes.

As we enter the first break, Trey accidentally lets loose a wave of ear piercing feedback that was so excruciating, half of the arena covered their ears out of pure reflex. The entire band even stops playing in response, albeit briefly. I’ll spare you the pain of playing it in this video. I’ve been to hundreds of concerts in my life and I’ve never heard feedback that painful, particularly from a band with as much live experience as Phish. Perhaps in an effort to remain true to the document, this brutal shreik made it onto both the official soundboard released to fans after the show, as well as the remastered release by Kevorian. Uh, thanks. I guess?

Moments later, you can hear Trey lasso his effects back in, and he makes it back in just in time for the first downbeat of the main riff.

Shortly after, we get to the first jam section of Tweezer. After the band sings the final line of lyrics, “Look who’s in the freezer, uncle ebeneezer,” they launch into a short section of improvisation that is full of tension. This mini-jam, is typically atonal, meaning that it lacks a tonal center or key. It is not major, or minor, it is no longer in the key of A, or any key for that matter.

The tag, or the phrase that propels the band into the next section, falls on the responsibility of Fishman. He plays a drum fill that brings everyone back to the main riff.

In the 2/28/03 version, Trey purposely overshoots the landing and doesn’t lock in at the same time the band does. Instead, he improvises a dazzling lick that does an exceptional job of raising the excitement in the room.

This effect, which my friends and I have always called the “hadron collider,” is a bit of a magic trick. Trey loops a short phrase and then pitch bends and time shifts it gradually, giving us this beautiful and swirling quality.

Putting the Fish in Phish

At the 5 minute 25 second mark, the jam officially starts. Meaning, every note played from here on out is collectively improvised. They don’t even know how they’re going to end the song. The plan, is that there is no plan. At the beginning of this jam, Fish comes in with a solid quarter note feel accentuated on his wood block. Trey immediately starts a lyrical pentatonic- based solo, starting moderately quietly and ramping up the intensity with every passing four bars.

At the 6 minute 11 second mark, Page shits his chordal approach to accent the Dorian flavor of Trey’s solo.

Dorian is known as the second mode of the major scale.

Roughly twenty seconds later after page comes in, we have the moment that shapes the jam moving forward. It’s the seed that allows the jam to blossom from a performance that is typical, to good, to legendary. This happens when Fishman improvises a beautifully intricate beat where he accentuates 32nd notes on his ride cymbal.

Every Phish fan has a moment where they’re watching the band live and realize “Oh yeah, this is why the band is named after the drummer.” This was that moment for 18-year old me.

A minute later, we have our third glow stick war, and one of the last ones that’s clearly audible in this performance.

At 7:22, Trey plays call and response with himself.

Over the next couple minutes, the band wanders. This is one of the biggest struggles for non-phish fans to understand. Most of us, when we listen to our favorite music, are used to the experience of every moment being a transcendent one. From Bob Dylan’s original All Along the Watchtower to Childish Gambino’s Redbone, we’re used to our favorite songs being a journey where every moment matters, where every note is essential and as meaningful as the last.

A Phish jam is closer to a hike in the woods. You maybe take a path that doesn’t necessarily seem attractive or exciting. But at the end of the trail, you end up on a beautiful overlook that you would have never discovered, had it not been for the seemingly boring turn you took a half mile back.

The wandering that we experience in this part leads to a brief lull in the jam at the 8:50 mark, where page introduces his classic hovering synthesizer sound. A few seconds later, Fish drops back into his intricate ride cymbal beat, which causes an emotional shift in the jam.

Fish’s beat is a bit of enigma, it’s rather quiet but it still grooves and is incredibly danceable. Although his rhythm is clear, it has a bit of a mysterious vibe that permeates the next few minutes of the jam.

At this point, Trey is holding a note and isn’t really playing a lot. I vividly recall him being in a moment of deep focus. He’s absorbing and listening to everything that’s going on around him.

Ego, Thine Enemy

Two weeks before this performance, I had picked up a copy of Kenny Werner’s Effortless Mastery at the McGill university bookstore. Trey’s moment of focus directly reminded me of a quote from the book, where the author is talking about improvising music while in an egoless, meditative state of mind, which he dubs the Inner Space. Werner states:

“The Inner Space is the place where joy, pleasure and fulfillment worldly and otherwise are available in unlimited supply. Acceptance of these gifts allows the flow to increase. Performances given from this state are said to be greatly inspired, leaving their audiences profoundly moved. A concert given by a performer who has attained this state is regarded as an event not to be missed.

When Miles Davis approached the microphone, he focused himself into that space before playing the first note. There would frequently be long silences between his phrases. In that time, you could see and feel him re-centering himself. That is very rare in jazz musicians today. That practice has the paradoxical effect of heightening people’s awareness and increasing the intensity of the moment.”

Werner continues,

“The highest state a musician can be in is a selfless state. Just as a river bed receives the great waters, we receive inspiring ideas. For many, becoming such a channel is little more than a myth or wishful thinking. Artists often have trouble getting out of their own way, and they must therefore struggle. They are often swept away by a river of mental and emotional activity. They are drowning in feelings of inferiority, inadequacy, and anxiety – the battle is mistaken for a holy war and romanticized.

But the struggle is simply with their ego…When I ask people which musician first attracted them to music, they often mention one who transcended these limitations. In the hands of such people, music has the potential of changing lives. Even when novices go to their concerts, they feel something opening inside.”

Phish have their own terminology for their state of egoless improvisation, called ‘the hose.’ This idea took shape when the band was opening for Santana in the Summer of 1992. Two years later, in an interview with NPR Trey said:

“We actually have exercises that we do, where we work on improving our improvising as a group. It gets rid of the ego. It’s an exercise to get rid of the ego. And the more that we do it the more we find that our improvisations are less concerned with showing off flashy solos or whatever, and more concerned with making a group sound. There’s a feeling that we always talk about. When we went out with Santana, he had brought up this thing about the Hose. … where the music is like water rushing through you and as a musician your function is really like that of a hose. And, and well his thing is that the audience is like a sea of flowers, you know, and you’re watering the audience. But the concept of music going through you, that you’re not actually creating it, that what you’re doing is — the best thing that you can do is get out of the way. So, when you are in a room full of people, there’s this kind of group vibe that seems to get rolling sometimes.”

Mike Gordon continues where Trey left off –

“It gets — It really starts to seem like It’s not the audience or the band. This Thing that gets rolling is It’s OWN Thing. When things are going really well, and a jam has taken off, there’s this feeling of motion that is created by the rhythm. And at that point my bass that I’m playing feels like this sortof vehicle, or like a hitch for me to hold on to, like someone would hold on to a um … Like if you were on a — I was thinking if you were on a ski lift, maybe. A chair lift. Or just something that would hook you on to the motion that’s going, and pull you along with it.”

Let the Music Pour Through You

The note that Trey holds at the 9 minute mark is the moment when the water starts rushing through that hose. Although there’s no surviving video of this performance, I remember the moment like it happened this morning. The audience could see him slow down and really center himself. He entered that moment of deep listening, and he spontaneously pours out this gorgeous improvised solo that perfectly matches the dark, quiet intensity of Fish’s drumbeat. Let’s take a listen, and pay close attention to the way Page’s lines wrap around trey’s like vine creeping around an Oak in effortless, natural conversation.

Fans have argued for decades what makes a jam hose-y or not. I’m sure many wouldn’t find this moment special, but for me, and many others, it remains a perfect encapsulation of the catharsis that Phish has been providing us for years. Although this jam is just getting started, we have a bit of conflict. Trey steps on his wah pedal in a frantic manner, which is sometimes a signal that a jam may be ending its course. Fish hears that and responds by hitting his China crash cymbal, which we’ve heard him use as a “ok, wrap it up b,” signal.

Trey decides to keep going and superimposes a new chord progression by playing Am – G – D. Perhaps this was in an effort to shift the jam into a new harmony, or perhaps it was just a cool sound that he wanted to explore. Check out the way that Mike hears Trey’s new harmony and matches it perfectly, while Fish is really hammering that China crash cymbal.

Regardless of these clashes, they collectively decide to keep the jam going, perhaps mostly due to Trey’s insistence. We have a few more seconds of wandering as the band collectively finds ideas and searches.

Around the 12:40 mark, Trey catches feedback and holds a D chord, allowing for another one of those centering moments where the hose starts to rear its psychedelic head. As Trey holds this chord, we hear Page improvising using a D major sound. Now, we can hear the jam start to turn Type II. This tweezer jam started in an A dorian mode, and we see the band shifting to the key of D based on Trey’s chords and Page’s lines.

Feel the (Slow) Burn

Trey starts repeating a D major arpeggio followed by a G major arpeggio, hinting a harmonic shift to a new progression involving the chords D and G. There’s no question that the other members can hear this change, but they don’t jump to address the chords instantly. Let’s listen as the band adopts a slow-burn approach and takes their time in addressing Trey’s implied chords. They patiently develop their harmonic backdrop as Trey digitally pitch bends his notes up into the stratosphere, giving way to a euphoric crest propelled by Fish’s delicate breakbeats.

This peak starts to peter out around the 16:22 mark and seems like it could end right there. Trey comes in with another beautiful lick and keeps the jam going. Fish drops in and out of double time at 17:16 as the band has ditched the D – G progression and decides to weave back and forth between D mixolydian and D dorian, driven by Page’s harmony and Trey’s lines.

Phish collectively groove and wander, until they find themselves in a syncopated circular funk groove initiated by Fishman around the 19:00 mark. Listen how Trey plays in an effort to copy the drums and completely nails it. Fish then continues to hop in and out of double time as the rest of the band grooves along with him.

The band searches and wanders some more, until Trey starts playing the chords D – F – G and back to D. In the key of D, this is a I – bIII – IV – I progression. Before, we saw that Trey gently played arpeggios and allowed the band to catch up with him and develop a new harmony. Here, he throws finesse out the window and becomes a power chord caveman that beats everyone over the head with this new progression.

Trey then rips through blues licks as the band sails through the last of the jam’s peaks. The signal to wind it down also comes from Trey, who digitally bends between the root and b7th (the notes D and C) to let the rest of the band knows that it’s time to land the plane.

Although the jam is over, the band isn’t done improvising, as we watch them spend the next few minutes splattering paint onto their canvas. Trey leaves us with a pitch bended loop, slowly decaying into oblivion as the audience is left speechless in its wake.

It’s Never Too Late

When I walked out of Nassau Coliseum on the night of February 28, 2003, something in me had changed.

As Kenny Werner said, a peak musical experience can positively alter the way you see the world, and that’s exactly what Phish did for me that day.

I felt like I had been let in on some big cosmic secret after having lived eighteen years in darkness, a slave to a mind languishing on autopilot. After that performance, I learned that every moment, regardless of your past, is an opportunity to completely reinvent yourself. And that the answer is always in front of us, around us, or more often than not, within us. We just have to close our eyes…and listen.

Leave A Comment