In the summer of 1987, Phish spent much of their time playing the bar scene in Burlington, Vermont. Just a decade later, they drew 70,000 fans to Limestone, Maine, where they threw a legendary festival called The Great Went.

On August 17, 1997, Phish played a version of their song Bathtub Gin, that is widely considered to be one of the bands best improvisations of all time.

Chapter Timestamps

************************

0:00 – Introduction

0:56 – The history of “Bathtub Gin”

1:34 – Connections between Trey Anastasio and George Gershwin

6:22 – What is a Type I Jam?

9:38 – What is a Type II Jam?

13:37 – Exploring Trey’s Improvisational use of Theme & Variation

15:52 – How each member aids in harmonic development

17:37 – Analyzing the peak of the jam

19:05 – Exiting the jam

20:15 – Final thoughts

When it comes to the word “jam,” so many people envision a meandering musical performance that is as forgettable as it is meaningless.

Whereas a good phish jam, particularly this one, is a transcendent spontaneous musical conversation that travels through multiple themes and movements. It is as thoughtful and compelling as it is a masterful display of musical creativity and discipline.

A truly memorable Phish jam won’t just defy your expectations as a listener, it will cause you to experience emotions that you didn’t know existed.

The History Of Bathtub Gin

Bathtub Gin combines music written by Phish guitarist Trey Anastasio, with lyrics by one of his longtime friends, Susanna Goodman. The album/liner notes for Lawn Boy mention that lyrics were “permission of Bret and Wendy,” who happen to be two of the main characters in the song.

Goodman’s lyrics paint a carefree psychedelic medieval world, complete with jesters, impatient royalty, and of course, bootleg liquor.

“Bathtub Gin” first appeared in the 1920s in the United States, as general term for brewing any kind of homemade spirit.

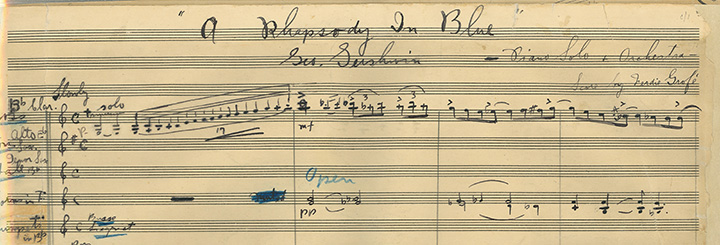

The Phish song happens to take an enormous amount of inspiration from a groundbeaking piece of entertainment from the ’20s, George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue.

Page McConnell’s jarring opening lines to Bathtub Gin are drawn from a dark portion of the first piano solo in Gershwin’s masterpiece.

Most famously, the chorus of Gin directly quotes a central theme of Rhapsody in Blue, one that is repeated throughout the entire piece.

Prohibition era slang, and musical quotes aside, these two songs are bound by one major compositional device: humor.

Humor as a Compositional Device

Its easy to hear that Gin is an inherently funny song, particularly in its outward circus-like bounce and whimsical lyrics.

And the song is full of little musical jokes, such as the extra beats between repetitions of the chorus, the harmonized major thirds that Trey and Page sing in the song’s main theme, creating a catchy light hearted dissonance.

Let’s not forget the irony of thousands of hippies relishing the thought of cleanliness.

Gershwin was well known for using humor in his compositions and Rhapsody in Blue is no exception.

The very beginning of the piece includes an inside joke between Gerswhin and Ross Gorman, the virtuoso Clarinetist in Pual Whiteman’s orchestra.

During a rehearsal, Gorman exaggerated the opening glissando and made it wail, purely as a gag, and Gerswhin thought it was so funny, he wrote it into the piece. It soon became one of the most iconic introductions in modern musical history.

Anastasio & Gershwin on Channeling the Sounds of Nature

Gerwshin told his first biographer Isaac Goldberg in 1931 how Rhapsody in Blue spontaneously unfolded in his imagination, while he was traveling on the train between Boston and New York for the opening of his musical comedy, Sweet Little Devil:

“It was on the train, with its steely rhythms, its rattle-ly bang, that is so often so stimulating to a composer – I frequently hear music in the very heart of the noise… And there I suddenly heard, and even saw on paper – the complete construction of the Rhapsody, from beginning to end…I heard it as a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America, of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our metropolitan madness.”

– George Gershwin to Isaac Goldberg, 1931

This idea, of being musically inspired by the sounds around us, is a similar, deep inspiration for Trey Anastasio. In an interview with Guitar World magazine in 2004, he was asked about his habit of staring up and over the crowd as he plays, and how it looks like he’s really listening to something.

“I don’t want it to sound ridiculous, but I definitely feel like I’m listening to something. [laughs] I have this feeling that there’s a pattern that exists. I really do believe this. I mean, I know it. I’m sure of it. Even right now if you listen, right in this room I can hear about a thousand layers of rhythm: the air conditioner, the air, the sound in my head. There’s tones. It’s all there, and it’s just the sound of life. And if you listen to it and play it, people respond….And when I’m playing onstage, I find myself looking out, not usually into people’s faces, but over their heads and up. And the endless possibilities, the depth of it all, occasionally will come to you.”

– Trey Anastasio to Guitar World, 2004

Looking at the Went Gin

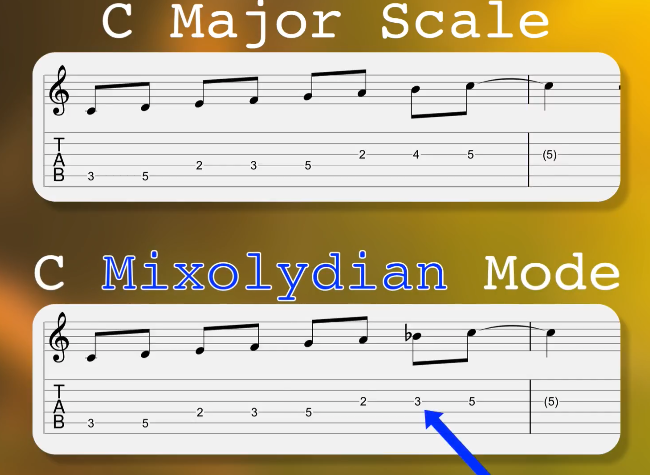

The jam in the Great Went Gin starts at the 4:44 second mark. This one starts the way pretty much all Gin jams do, with the band casually improvising in the C Mixolydian mode.

C Mixolydian is similar to the C major scale.

But the seventh degree is flattened, giving a more laid back sound.

This idea of, looking at modes as modified major scales, is known as parallel construction.

Soon, we’ll see how the band uses this as they collaboratively shift between C major and C mixylodian, like they’re hopping back and forth between between two different, yet clearly related worlds.

Just a few seconds into the jam, we start to hear some purposeful interplay. Trey quotes the melody (5:02), and Fish starts to playfully stagger the beat (5:02 – 6:15). Trey then staggers the melody rhythmically (6:29).

Fish drops into half time, Trey doesn’t particularly want to, as evidenced by the glance he shoots Fishman (6:51)

Trey quotes the melody again at (7:21) is still not happy with Fish dropping in and out of half time.

This kind of push and pull between the drums and guitar was a thorn in the side of the band, as well as a potent source of chemistry. As Trey told Salon:

“In the early ’90s, we started realizing we were having tempo battles onstage. Fish would decide he’d lay back, and I’d want to rush. Every band who’s ever improvised goes through this. Then someone gives the angry glare. What are you doing? Oh my god! The gig is falling apart because you’re rushing! “

Trey fist pumps in approval once Fish develops a strong, consistent groove on the drums around the 7:30 mark.

Fishman’s new beat causes a spark in the band’s creativity. The jam takes its first major turn just a few seconds later, when Gordon spontaneously composes a bassline that takes them out into a new progression. He starts playing the notes C-F-A-G (7:36-7:56).

This is the turning point in the jam, the impetus for the very peak and substance of the performance itself.

Up until now, the improvisation in Bathtub Gin has been Type 1. The band has been improvising in a fixed chord progression or mode.

The notes that mike has been playing, C-F-A-G, are hinting of changing from C mixolydian to C major. Let’s look at our C major scale again.

If we take every third note and put it on top of the each of our scale, we get Dyads. Two note chords. In this case, we’ve created dyads with major and minor thirds.

If we take the fifth note and put it on top of our dyads, we get triads, that we commonly call chords.

You can mix and match these chords in countless ways to create a chord progression. For example, the building block of popular music in the last 100 years is the the I-IV-V (one four five) progression, which in the key of C would be C-F-G.

Going Type II

As we mentioned before, Gordon is playing the notes C-F-A-G, which in the key of C, means that he is playing the root notes of a I-IV-vi-V progression, or the chords C – F – Am – G. Mike is sowing the seeds of a Type II jam, where the original chord progression or mode is abandoned, and a new one is established essentially out of thin air.

Trey hears Mike developing this new harmony and stops soloing in the traditional sense (8:08-9:08 and beyond). He locks into a rhythmic pattern. This creates a “harmony hole.” Instead of playing chords or notes that imply chords, he is just playing the note C in different octaves. It now is up to Page and Mike to develop the harmony, because Trey has consciously chosen not to. This was very intentional because the harmony is beautiful yet simple, and Trey stays out of the way to see where Page and Mike will take it.

Mike has still been playing C-Am-F-G.

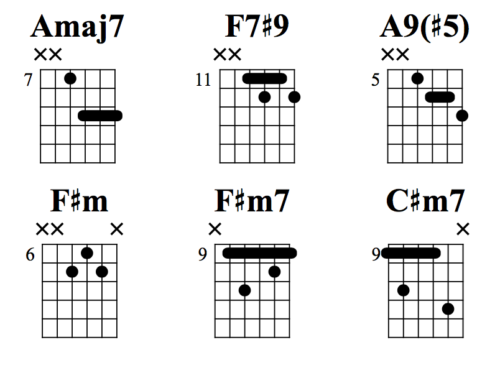

At 10:18 the harmony that Mike has been implying evolves into C-Am-F thanks to Page, who joins him by actually playing these chords underneath Trey.

We can say that this is the moment, where the jam distinctly turns Type II. The C Mixolydian sound, which was the original harmony of Bathtub Gin has been abandoned, and a new improvised harmony has developed, a C-Am-F progression.

This whole time, Trey has been repeating a rhythmic figure and he starts slowly developing melodies by performing a theme and variation on a four note melody.

Although these notes are simple, this creates a beautiful tension and release over the three chord harmony.

Trey’s melody has really been focusing on the notes C and G. Over the C chord we still have a C chord. But over the Am, the melody creates an Am7 chord, and over the F chord, it creates an Fmaj9 chord.

All three of these chords can be found in our C major chord scale. All we have to do is stack the 7ths to get the and Am7 chords. And for the Fmaj9, we add the 9ths to every chord.

Son, You Left the Hose On

In a move of complete and utter telepathy, Page abandons the harmony by going back to a Mixolydian sound 11:44 -12:04. The rest of the band immediately hears this and stops playing the progression as well and start teasing a C mixolydian sound to complement what page is playing.

Trey ceases his C major based melody, and instead focuses on notes that are friendly to both C major and C mixolydian. This allows him to fit into the groove while avoiding notes that may clash.

However, this doesn’t last long, and page and mike bring back our four chord harmony around 12:05.

At this point, Page and Mike step aside and support Trey as he builds intensity by throwing in some fierce blues licks over the C Am F progression.

The band takes note and plays with more and more intensity, building the jam to a soaring peak.

He finally lands at the jam’s highest peak, where he composes a simple, yet triumphant ostinato melody.

Notice that his melody is really focused on the note C, which is the root of the C chord, the minor 3rd of the Am chord, and the 5th of the F chord. This is why this theme makes us feel like we’ve arrived at home – the physics of Trey’s lines give us a big sense of stability. The repetition creates tension and excitement and makes us feel like the moment could last forever, and often, we wish it does.

Making a Graceful Exit

After some more peaking Trey starts playing trills, which is often signals to the rest of the band that he wants to end the jam or move to another section. That’s exactly what happens.

Most Gin jams end with the band returning to the main chorus melody, and then slowing down until they all crash into a big Bb chord

However this version, Trey then plays rhythmic octaves and Fishman reacts by playing a rhythm that morphs into the classic country/bluegrass fast train beat. The band seamlessly segues into to their arrangement of Bill Monroe’s “Uncle Pen” .

The Went Gin will always stand as a monument, to Phish’s ability to spontaneously craft a masterpiece out of seemingly thin air, and for the audience’s ability to trust them to take us on a journey we’ll never forget. Because it’s never just about the notes or the scales, or the chords, but it’s about our ability to come together and appreciate the magic that they create.

Leave A Comment